Cheese from the Adriatic Alps

Cheese production in the Adriatic Alps has developed over many centuries. Each valley has its unique speciality but they all share the same mountainous obstacles.

Without dairy farmers and cheese makers who work with the utmost love and passion we would not have the outstanding products that we so often find in top international gastronomy. The sheep's cheeses of the Nuart family from Austria's Lower Carinthia region are so popular that you have to pre-book them. Their famous 'Black Sheep', a fresh cream cheese rolled in wood ash and sea salt is always in high demand. The fact that the Nuarts use sea salt instead of mountain salt shows their attachment to the Adriatic.

'Horse apple' is what Astrid Zerbst from Gailtal calls one of her cheese specialities made from goats' milk. This Austrian cheese maker, who is as charismatic as she is passionate, has achieved nationwide fame for the quality of her cheeses. When asked about the secret of her success, she is modest, "Our goats are only kept outside and are allowed to eat what they want. When it comes to foraging, they are the experts, you can smell it in their milk."

Mountainous obstacles

The spicy Gailtaler Almkäse (Alpine cheese) is produced on 13 alpine pastures and is so precious that it is now protected by the EU. Like many alpine cheeses its origin arose from a necessity of alpine pasture management, for example, the transport of fresh milk and butter across the mountains was impossibly slow and difficult in the early Middle Ages, hence the milk was preserved on site in the form of cheese.

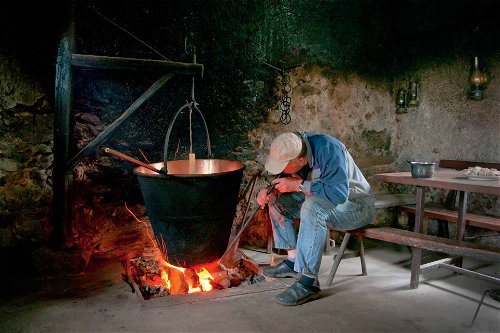

Transporting milk isn't the only obstacle for alpine cheese makers. Whey is a by-product of cheese production and in the valleys would be used for pig fattening, but the mountains are too steep for pigs so the Gailtal dairy farmers created Almschotten, a smoked cheese derived from whey rather than curd. Schotten is a dialect term for whey.

Smoking and Maturing

Friuli, in Italy, also has a tradition of smoking cheese to give it more flavour and spice. A speciality from the Canal Valley and Carnia is smoked ricotta, which has a brown surface but is white and grainy on the inside. During production, whey is added in addition to fresh milk thus making the most of the raw materials available. It can be sliced when fresh or grated over food when it has become a little more crumbly, which it does over time. It has a sweet, slightly tart taste with a hint of smokiness.

Montasio cheese is matured in karst caves. Karst caves are formed by water eroding soluble rocks such as limestone, marble and gypsum. Montasio is named after the plateau of the same name in the Friulian mountains, but it can also be produced outside Friuli and has established itself from the Carnic and Julian Alps to the plains of Friuli and Veneto. It is a spicy, semi-hard cow's milk cheese which is delicate and soft when young and reminiscent of Parmesan when it has matured. (Stravecchio indicates the cheese has matured for at least 18 months).

Maturation in caves gives the cheese a special flavour that no air-conditioned warehouse can match. Cheese icon Dario Zidarič swears by the special conditions in the 70-metre-deep karst cave where he stores his Jamar cheese. This is a semi-hard, crumbly cheese with a grey-brown rind that sometimes turns blue. The intense and persistent aromas are reminiscent of the herbs the cows eat, the Karst cave and the nearby sea.

Slovenian Cheeses

The Soča valley, famous for its turquoise river with its surrounding mountains, is probably the most important region for Slovenian cheese. Best known is the hard-fat cheese Tolminc. It may only be produced in the area of Zgornje, the northernmost part of the Soča Valley. The history of the sweet and spicy cheese goes back to the 13th century and is richly documented as a means of payment to landlords. As with Gailtaler cheese, the origin of the cheese culture lay in the fact that milk was available in abundance and had to be preserved.

At the northern end of Soča Valley is the village of Bovec, which is known for a spicy hard cheese made from sheep's milk, Bovški sir. Like many mountain cheeses, it is only produced from spring to autumn, as long as the sheep can find fresh herbs and grasses in the Triglav National Park. Only raw milk from the native Bovška ovca, a breed of domestic sheep originating from the upper Soča valley, is allowed to be used.

High on the Slovenian alpine pastureland, not far from the Austrian border, is Velika Planina, one of the largest alpine shepherds' settlement in Europe. Here the local speciality is a mild, pear-shaped Trnicˇ cheese, made from curd and whipped cream. The story handed down is of lonely dairymen who missed their wives along with their physical assets and so shaped the cheese in the form of breasts. They decorated their cheese with self-carved stamps and offered them as gifts to their sweethearts when they hiked back down into the valley.

A cheese speciality with a strong character comes from the area around Bohinj in the Julian Alps, near the border with Italy and Austria. Mohant is a semi-soft cheese made from cow's milk that is characterised by pronounced spiciness, sharpness, bitterness and an almost pungent aroma. Lovers of mild semi-hard cheeses may not enjoy it, but for cheese aficionados, Mohant is a sought-after rarity. The first written record of this cheese dates from 1925, traditionally it would be served with unpeeled boiled potatoes.

The Alps of the Adriatic may be remote and less familiar to us than those of France or Switzerland, but this impressive and beautiful landscape has a wonderfully diverse cheese culture that has evolved through necessity and is still rooted in the survival of old practices and native breeds.

Many of the producers are small scale, artisan farmers, but thanks to the Slow Food Movement and their international catalogue The Ark of Taste which aims to protect and promote endangered heritage foods, their ways and wares are being protected and recorded. We consumers can do our bit too, by seeking them out, tasting them, cooking with them, sharing them and enjoying the amazing quality and uniqueness of alpine cheeses.