Coffee: Our Favourite Elixir

Coffee almost is a magic potion. But it is also big business. Here is a brief history of coffee and an exploration of the most important coffee-growing regions.

Coffee is as much a part of our lives as electric light and human rights. It gets us going in the morning, perks us up during the day and even rounds off dinner in the evening. We love coffee. But how did it become such an integral part of our culture? Who discovered this combination of deliciousness and stimulation that makes us love coffee so much?

Goats in Ethiopia

It's a long way from the fully ripe, red fruit on the bush to the roasted bean. Legend has it that goats were the first creatures to enjoy coffee. Somewhere in Ethiopia, a shepherd observed his animals eating the fruit of a coffee bush. A few moments later, they clearly were livelier and more alert than the abstinent goats. Another source attributes the discovery of coffee’s stimulant to Prophet Mohammed. Yet another story holds that birds pecked coffee fruit from the bush and stopped sleeping. Most researchers, however, agree on one thing: about 1200 years ago, people drank hot coffee for the first time –they had somehow discovered that the fruit develops alluring aroma when roasted over a fire and is made into an infusion.

It is also undisputed that the coffee plant originated in Africa. Exactly which country it came from is unclear, but it is most likely Ethiopia or Yemen. It is presumed that slave traders first took coffee to Arabian lands from whence it conquered the world. The name “mocha” is thought to be derived from Al-Mukha, a port city in Yemen, which was central to coffee trade. The word coffee also shows the historic influence of Arabia, going back to the Arabic qahwa. It was from Turkey – the first coffee house opened in Istanbul in 1554 – that the aromatic wave spilled over into Europe.

Coffee Beans are Flavour Bombs

Five hundred years later, coffee has become a lifestyle staple of immense proportions – today even prams come fitted with coffee cup holders. Contemporary coffee bars gleam with massive, brightly polished stainless steel machines at which expert baristas conjure up caffeine treats. A few deft movements and coffee flows into the cup, crowned by a firm crema, that white foam of expertly made espresso. Hundreds of aromas are released from the small beans – more than from wine.

But coffee fashions are also subject to change: the Scandinavian coffee movement means that up-to-date coffee aficionados no longer drink their espresso dark roasted and almost burnt; they prefer as light a roast as possible so that a wider spectrum of aromas can still be tasted.

Coffee Climate

Botanically speaking, the cultivation of coffee is only possible in a narrow strip of latitudes around the equator: the coffee belt. Coffee plants thrive best in an alternating climate of humidity and dryness, without large temperature swings and sufficient rainfall. This predestines some countries for cultivation: coffees from Latin American and some African countries are prized for their quality and – as can be the case with wine – altitude can be a quality-boosting factor. Coffee nerds swear by Ethiopia and Kenya. Especially coffee grown by smallholders with excellent farming practices and hand harvest is exquisite.

Sustainability

When we talk about these coffees, they almost always belong to the Arabica type. In contrast, there is coffee from the Robusta family, which botanically belongs to a different genus. Vietnam and Brazil are the predominant growers of Robusta coffee. Brazil, as the largest coffee producer in the world, is generally known for mass-produced coffee which is mainly machine-harvested. You have to go to some length to find excellent coffees there, but the Italian roaster Illy has been making that effort for almost 20 years. Their Ernesto Illy Award honours excellent producers for their coffee quality. Illy has similar programmes in Colombia where the lucrative but illegal cultivation of coca plants is still rife. It is paradoxical: although coffee quality has never been as high as it is today and connoisseurs pay top prices, the growers themselves are in crisis. Coffee roasters are responding to this with a transparency offensive: major roasters are committed to communicating the purchase price of the beans to their customers. Then there is the environmental aspect, for example in the touchy area of capsule coffee. Lavazza, for instance have developed new capsules under the Eco Caps label that are compostable.

As far as preparation methods are concerned, the most original way of drinking, originating from Ethiopia, is still practised: Roasted beans are crushed with a mortar and brewed with hot water in an earthenware pot, the jabana, before the drink is poured into small cups. It is precisely this preparation as mocha that is on the rise again: Lavazza, for example, has just launched a modernised version of the cult Carmencita pot, which allows you to brew your coffee directly on the stovetop. Filter coffee has also enjoyed a resurgence.

The Plight of the Farmers

The price of raw coffee has hit rock bottom. Many farmers can no longer make a living from their work and are leaving their plantations behind.

Almost three years ago, the price of coffee finally crashed: On 18 September 2018, traders on the New York Stock Exchange paid just 95 cents for a pound of raw coffee – the lowest price since 2005. In 2015, the price was still at $2.20 and while the prices has now stabilised somewhat, it has not recovered. While the billion-dollar coffee business generates high profits for some stakeholders, for many farmers at the lower end of the value chain it has long been a matter of survival. Experts estimate that the cooperatives have to earn at least $1.50 per pound of raw coffee to cover their costs. Because prices have been far below this mark for a long time, the farmers' plight grows constantly. They can no longer make a living from their work and any reserves they may have had are depleted. Andreas Felsen, a Hamburg-based coffee roaster says: "First they save on their fields. Then they take their children out of school. Then they save on food and then finally they leave their country."

In fact, much of the migration from Latin American countries is due to the coffee price crisis. Many abandoned coffee plantations in the country bear witness to this. There are several reasons for the drop in prices, but chief among them is a simple denominator: overproduction. Brazil, the largest producer of coffee, doubled its annual production in the past 25 years. Here, farmers harvest mainly with machines which keeps wages, a key cost factor, low. Vietnam, once a marginal coffee producer, has now grown into one of the dominant players in the market, partly due to short-sighted development aid. Here, wages are a fraction of what they are in South America. Coffee connoisseurs who spend three euros and more on their cappuccino are often unaware of the farmers' crisis. What can they do about it? Relatively little, says Andreas Felsen. He sees it as the industry's turn to guarantee minimum prices through fair trade. "The best thing is to ask your roaster how much money ends up directly with the farmers." Those who take the Fairtrade approach seriously should share these facts transparently. Good coffee costs money, and coffee lovers should be aware of that.

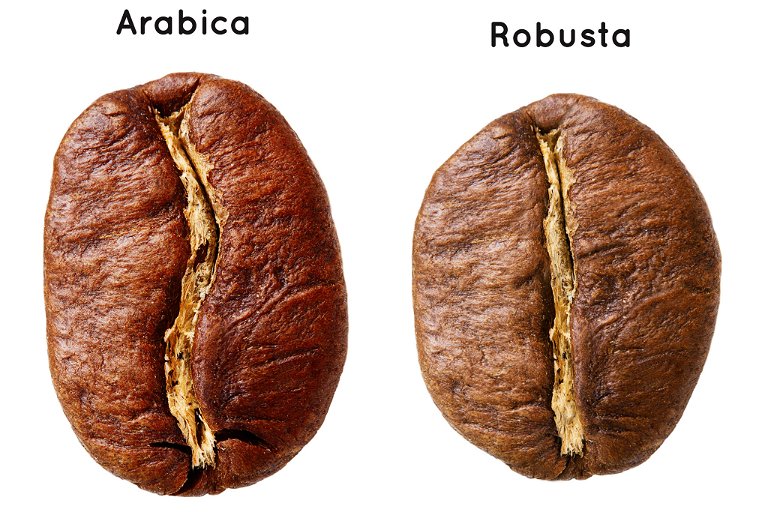

Arabica vs. Robusta

If you take a closer look at your coffee package, you will quickly come across the terms Robusta and Arabica. Their names already offer some clues when it comes to flavour: As the name suggests, Robusta coffee stands for more solid flavours. Its body is fuller and the crema looks nicer. However, the most expensive and exquisite coffees you can get are almost always Arabica varieties. They grow at altitudes of up to 2000 metres /6560 feet and are more demanding in terms of soil and climate. Because of the altitude, these Arabica plants ripen more slowly which favours the synthesis of aromas.

Many coffee drinkers tolerate Arabica coffees better than Robusta varieties, which usually have more bitterness. In many espresso blends, a small proportion of Robusta is used in addition to Arabica to combine the advantages of both varieties. Globally, the share of Robusta is 35 to 40 per cent, with the largest producers being Vietnam and Indonesia. Apart from Brazil, the most important Arabica countries are Colombia and Ethiopia. Interesting for caffeine junkies: Robusta varieties usually have twice the amount of caffeine as Arabica.

Die beliebtesten Röstereien

Adrianos

Kaffeegenuss aus Bern, mit eigenem Lokal.

Kornhausplatz 11, 3011 Bern

T: +41 31 3188831 www.adrianos.ch

Black & Blaze

Kleine Kaffeerösterei auf der Forch. Nachhaltige, faire und technisch versierte Produktion. www.blackandblaze.com

Blaser Café

Berner Familienunternehmen mit langer Tradition. Vielfältige Auswahl an Spezialitäten, inklusive Pads.

Güterstrasse 6, 3008 Bern

T: +41 31 3805555, www.blasercafe.ch

Henauer Kaffee

Seit 1896 im Kanton Zürich ansässig. Auserwählte Röstungen in Bio- und Demeterqualität.

Hofstrasse 9, 8181 Höri

T: +41 44 8611788, www.henauer-kaffee.ch

Kafischmitte

Saisonales Angebot, frisch geröstet, transparent und fair gehandelt.

Bädligässli 4, 3550 Langnau

T: +41 76 2021771, www.kafischmitte.ch

La Semeuse

1000 Meter über dem Meer geröstet, Bioqualität, legendärer Mocca.

T: +41 32 9264488, www.lasemeuse.ch

Miró

Kleine, aber feine Rösterei mit Café im Kreis 4. Mehr Geschmack, weniger Röstung.

Brauerstrasse 58, 8004 Zürich, www.mirocoffee.co

Pausa Caffè

Kleine, familiengeführte Rösterei. Hervorragender Espresso.

Via Capidogno 87, 6802 Rivera

T: +41 79 4071686, www.pausacaffe.ch

Stoll

Eldorado für Kaffeefans: extravagante Third-Wave-Coffees.

Austrasse 38, 8045 Zürich

T: +41 44 4633378, www.stoll-kaffee.ch

Schwarzenbach

Zürcher Kaffeeinstitution seit 150 Jahren, vielfältige Auswahl an Röstungen.

www.schwarzenbach.ch