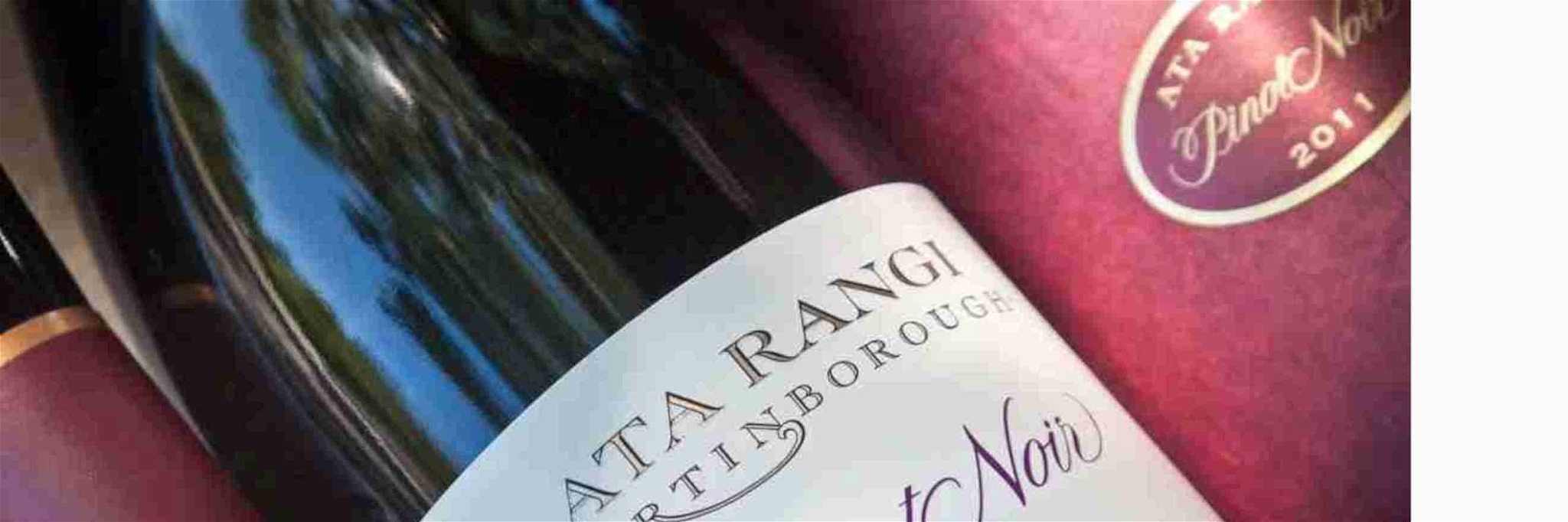

NZ Pinot Noir in the Spotlight at Ata Rangi’s 40th Birthday

One of New Zealand’s top wineries celebrates a landmark birthday. Ata Rangi was planted in 1980 and while the pandemic prevented a physical party, it held a tasting to mark the occasion.

Ata Rangi from Martinborough ranks among New Zealand’s top Pinot Noirs. It was the name that put the once sleepy township on the international map and has helped shape the country’s wine industry.

Such is its status that we forget how recent New Zealand’s success with Pinot Noir is – and therefore all the more remarkable. It was in 1980, 41 years ago, that a young dairy farmer, Clive Paton, bought a stony piece of cattle pasture – and the rest is history.

Midlife crisis

Mackenzie Paton, Clive’s daughter, explained: “Dr Derek Milne [of New Zealand’s Department of Scientific and Industrial Research] in 1978 published a scientific report looking at the soils and climate in this tiny town in the middle of nowhere. He roped in my dad who was a dairy farmer with a midlife crisis who did not want to milk cows for the rest of his life, so he bought land in 1980.”

Smuggled goods

What is even more remarkable is that Paton planted the so-called Abel clone. This is a clone that was rescued from the biosecurity incinerator at Auckland airport when another winegrower wanted to smuggle stolen Pinot Noir cuttings into New Zealand – apparently they were illegally cut from one of Burgundy’s finest grand cru vineyards.

The customs officer, Malcolm Abel, was also interested in wine and put the cuttings through quarantine and propagated them. Today, the quality of this particular Pinot Noir clone is beyond doubt.

Dairy equipment

Why even resort to – at the time – questionable cuttings to plant a new vineyard? Well, in the early 1980s there was no real wine industry in Martinborough, let alone vine nurseries or any real wine infrastructure. “There was not an awful lot going on apart from meat, dairy and wool in those days,” Paton said. Much of the new wine was also made in used dairy equipment.

Alongside Ata Rangi, others also planted vineyards: notably Dry River Vineyard planted by Dawn and Dr Neil McCallum in 1979 and Martinborough Vineyard, also in 1980, by Duncan Milne. Today there are about 45 wineries – all making wine from those pebbly soils.

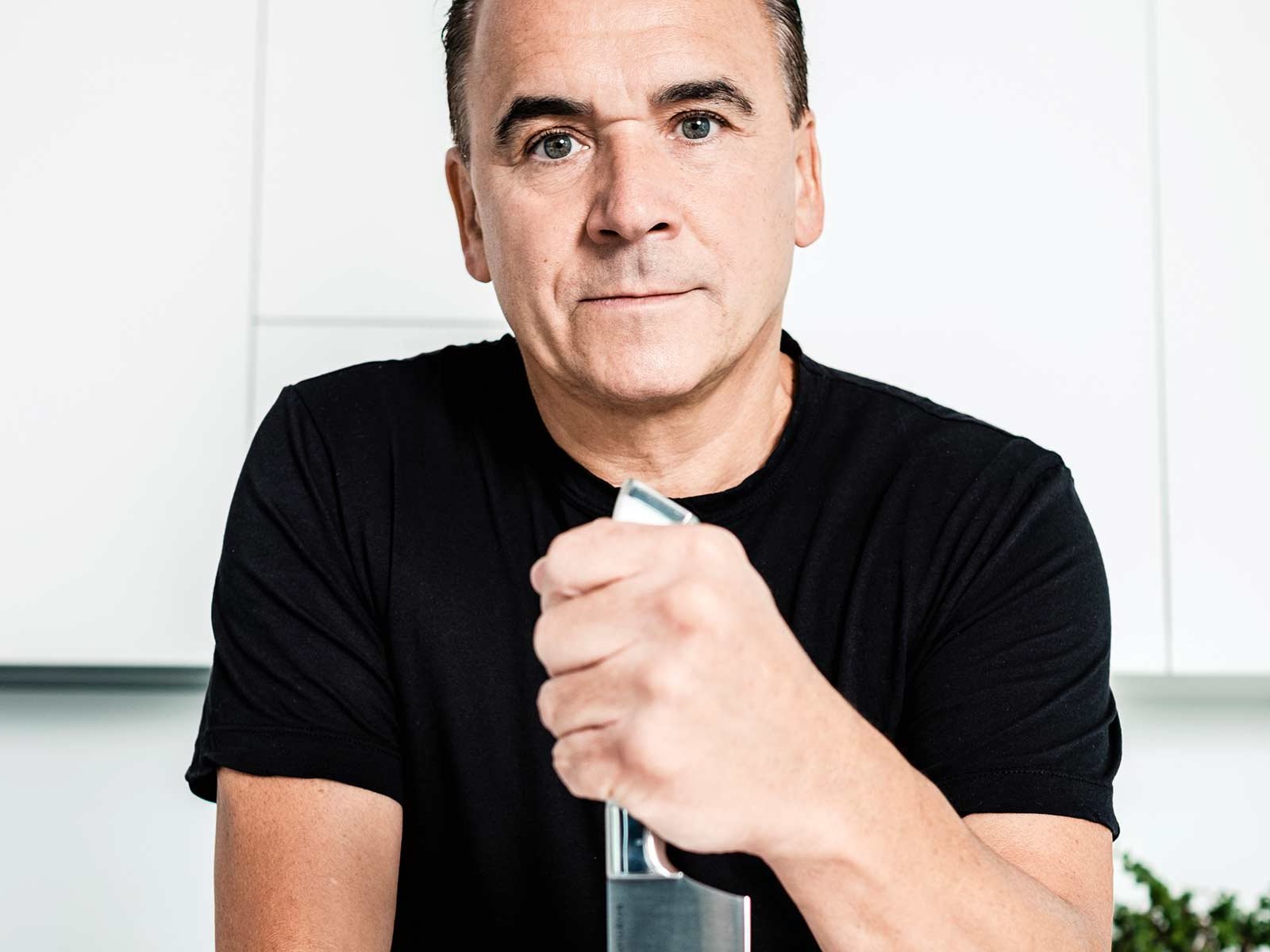

Star winemaker, star soils and fossils

Winemaker Helen Masters started at Ata Rangi in 2003 but her connection to the vineyard goes back further. She was and is key to the success of these wines that speak so very much of place. “We used to talk about this just being an alluvial gravel terrace, but the soils are distinctly different. There are these long, brown smudges, some compacted seams of clay, that run through the gravel terrace. How the clay interacts with the gravels really has an impact on the wine,” Masters said. “25 million years ago this was seabed, and in the hills around Martinborough there are oyster shells. Rather than clean river gravels you find stones that have small fossils in them.”

Antarctic freshness

The other aspect, Masters said, was the climate: “The valley is completely open to the Antarctic. The biggest factor impacting our wine is how cool we are in summer. The most difficult time is spring with really cold southerly breezes coming right up through our valley. All the wines today, if I can give you a sense of Ata Rangi, of our style, it is that this orientation to the south impacts our wines.”

Rosehip, liquorice and sweet hay

The free draining gravel soils, the cool climate and Abel clone thus form the style that made Martinborough famous. The cool weather at flowering often means poor fruit set and thus rather loose bunch architecture in the grapes.

Masters said that a ripe bunch of grapes of the Abel clone on average weighs 100g in Martinborough and 200g in Central Otago. “Many berries are very small, how the berry is exposed to wind and sunshine, means that in most years the grape skins are firmer than in any other New Zealand region – and this is partly what defines us. Because we have those smaller berries, it is about balancing the tannin structure. Our drive is to really show that more savoury character of rosehip and liquorice, and one character I have really come to appreciate in Ata Rangi is the smell of sweet hay in summer.”

McCrone

In 2001, the McCrone Vineyard was planted. “McCrone is really different with layers of clay that sit between the stones,” Masters explained. “We are really starting to see an expression here. We were amazed how it showed itself from early on. We tend to get a little bit more aroma, something really robust, an iron note.

The planting mirrors the clonal mix of the original home block with a predominance of Abel. ”The difference between the home block planted in 1980 and McCrone, just 400m away, is thus down to soil. 2013 was the first separate bottling of McCrone, but “2015 was the first vintage I got really excited about,” Masters confessed. “I very much try and respect this difference, I think it is really important that the year shines through, so no yeast, no enzymes, we don’t fine we don’t filter.” For die-hard Pinot fans, however, it is the Ata Rangi home block that expresses that much-loved Martinborough savouriness best.

The pandemic prevented a proper 40th celebration in 2020 on the vineyard but speaking via video link to London, Masters got her point across perfectly by presenting two mini-verticals: Ata Rangi Martinborough Pinot Noir 2013-2019 and McCrone Vineyard 2015-2017. “Last year we celebrated 40 years on the land. It’s been really nice to look back,” she said and smiled. Falstaff also had a big smile after tasting the wines.

You can also read our