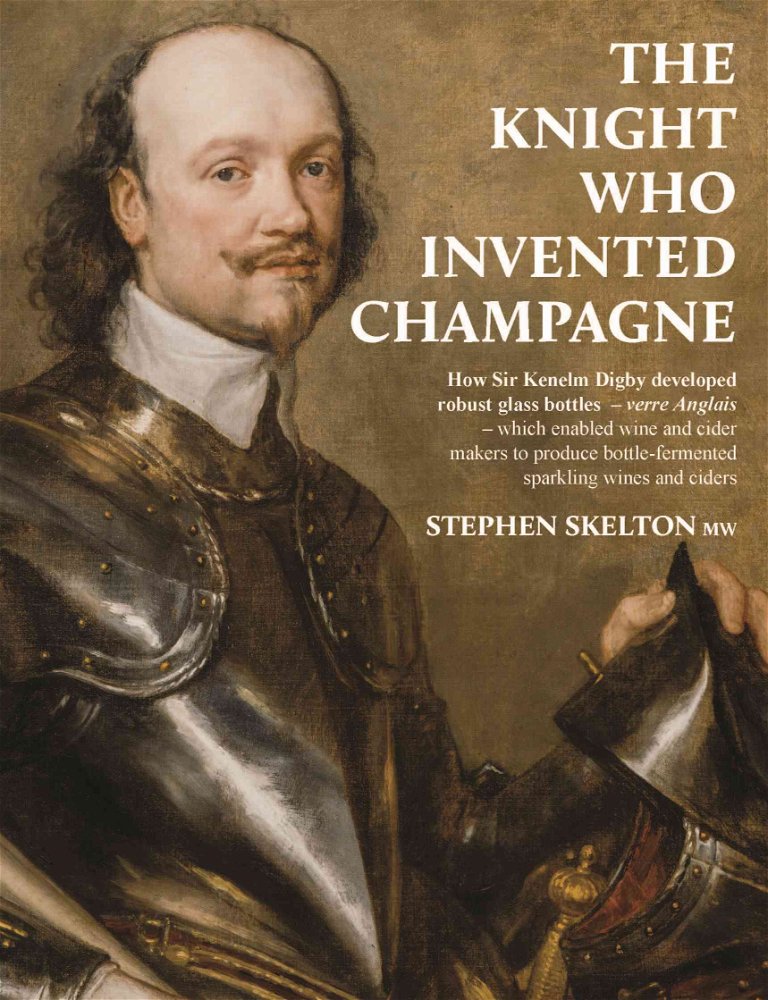

Of Bubbles and Bottles: The Knight Who Invented Champagne

Long intrigued by the history of sparkling wine, our author’s detective work pieced together a vital chapter in the genesis of sparkling wine. Here he introduces his book 'The Knight Who Invented Champagne'

The allegation of how “the English apparently invented the méthode champenoise” – the technique of adding sugar and yeast to still wine to make it sparkling – has long haunted me. Was it true, could it be true, how could it be true? The most celebrated Champenois, the monk Dom Perignon, is often credited with this discovery, so surely not the English?

“Brisk” Wine

So I started digging: we know for certain that in 1662 Dr Christopher Merret read a paper at one of the nascent Royal Society meetings in which he revealed that “our coopers of late” had been using “vast quantities of sugar and molasses” to render their wines “brisk and sparkling” – something that both purveyors of wine and makers of cider throughout Britain were doing to fizzy up their offerings.

However, adding sugar and yeast to create a sparkling wine needs something else – a structurally sound bottle, with a closure, in which to capture the bubbles, namely the carbon dioxide created by the secondary fermentation. For this, you need a strong bottle. I therefore set out to find facts about the making of such a strong bottle in the middle of the 1600s – almost a century before the French started selling the vin gris de Champagne in bottles made à la manière d’Angleterre.

Smelting: from Wood to Coal

My research led me to Admiral Sir Robert Mansell, a man who had started his naval career by helping defeat the Spanish Armada in 1588. By 1615, he was advising James I and persuaded the King to issue a proclamation forbidding the use of timber for smelting – glassmakers and iron-masters being the biggest users. Fortuitously, Mansell owned coalmines and colliers (ships) with which to supply the glassworks and iron foundries which moved from woodland sites, where timber was plentiful, to sites in estuaries and on rivers where coal, plus the bulky raw materials for glass and iron manufacture could be more easily delivered.

Sir Kenelm Digby

I also investigated the claims made in 1661-2 that another knight, the knight of the title of my book, had invented glass bottles some 30 years before that date: Sir Kenelm Digby. A man with an endlessly inquiring mind, glassmaking was amongst his many hobbies. Digby had a life of disasters and triumphs: he lost his father, one of the ten Gunpowder Plotters surrounding Guy Fawkes, to the hangman’s noose.

Triumph followed when he became a close friend of Charles I and a member of his Privy Council. The role played by Digby in the development of both strong glass and, more importantly, of strong bottles, is less well documented than one would like, save for the inquiry by the Attorney General in 1662 that confirmed that Digby had been involved with bottle making.

My book covers the start of the Industrial Revolution, the move from water and wind power to coal, and the very start of the manufacture of a product, a bottle, that was in its day as revolutionary as mobile telephones were to us when they first appeared: today both are so commonplace we barely notice them.

Click here to Stephen Skelton's book The Knight Who Invented Champagne