The Long Road to Germany's Grand Crus: Grosse Gewächse

Ever read the terms Erstes Gewächs or Grosses Gewächs on a German wine label? Here we trace the evolution of this private German classification, established in 1999 by the VDP, Germany's association of elite estates.

Bettina Bürklin-von Guradze of the famous Bürklin-Wolf estate in the Pfalz region remembers her mood very well when she took over her family's winery in 1990, "German wine had no reputation, and we had large quantities in the cellar. In short, we saw no future for this way of doing business and so we asked ourselves the central question: what actually is the most valuable thing we own? And it was very easy to answer: the vineyards. Kirchenstück, Jesuitengarten, Pechstein, and a dozen others. Our ancestors knew exactly what they were doing when they bought these vineyards. Sites like these were the capital of German viticulture, only the awareness of it had been lost."

Every wine lover knows and respects the classifications of Burgundy and Bordeaux; one knows (or can look it up in case of doubt) that Château Lafite-Rothschild, for example, ranks higher than its neighbour Duhart Milon, or that a Chambertin comes from a particularly privileged grand cru site, while a Gevrey-Chambertin Villages comes from the same commune, but not from the best vineyard of the place, but from one or more sites within that village.

Both classification models date back to the 19th century and have created both profile and prestige over the past 150 years — even for those whose vineyards tend to be on the lower levels of the classification. If you look at the prices for vineyards, a hectare of Bourgogne (i.e. the regional appellation) is about six times more valuable than a hectare of another French vineyard with no classification. The mere fact that the vineyards are critically inspected and ranked into quality classes creates confidence and demand on the market.

The beginnings

"Once we understood that we couldn't just carry on like this, thoughts quickly turned to the subject of classification," Bürklin-von Guradze recalls further, "and that's when we came across Bernhard Breuer, a winemaker in Germany's Rheingau region, a clever and visionary mind who had already delved into the subject."

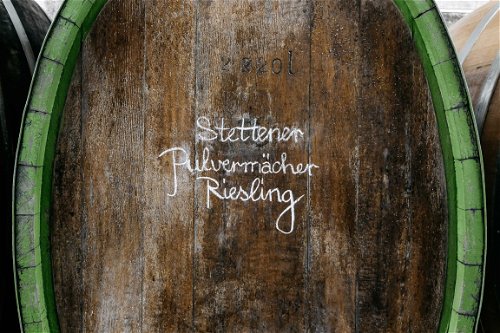

Breuer had (co-)founded an association in 1984 that can be seen as the impulse behind German classification: the Charta association. According to its statutes, Charta Riesling had to come from "the best Rheingau vineyards". The wine could not be released onto the market until at least twelve months after harvest. This rule still applies to Grosses Gewächse (GG) wines today. "Bernhard Breuer was the spiritus rector," Bettina Bürklin-von Guradze says. "He may even have been the one who suggested that we Pfalz winemakers follow the four-tier classification model from Burgundy.

The heartland of the Pfalz wine region, the Mittelhaardt, is not unlike Burgundy in the way the vineyards lie: on the slopes of a protective mountain range, sloping down towards a river plain. In 1994, a small group of VDP member estates, i.e. Christmann, Mosbacher, Bürklin-Wolf and Koehler-Ruprecht, published a Declaration of the Four, which was the opening shot for the modern-day vineyard classification of the Pfalz region. As early as 1999, 80,000 bottles of Pfalz Erstes Gewächs went on sale, eyed suspiciously by the wine inspectorate. At first, attributes such as 'G.C.' and 'P.C.' (modeled on the French terms grand cru and premier cru without actually spelling them out) — protected by Bürklin — and Erstes Gewächs were not allowed on the label, in some places there even was trouble with the authorities when such designations appeared on price lists or in sample booklets. Nevertheless, other wine regions also founded a Comité Erstes Gewächs, and the name Erstes Gewächs was to prevail (for the time being).

However, in the Rheingau of all places, in Bernhard Breuer's home region, Erstes Gewächs took an unforeseen turn. In order to establish this designation legally and for all winegrowers, the federal state of Hessen demanded a scientific foundation of the classification. This was carried out by the University of Geisenheim along parameters that were already rather questionable at the time. The consideration and emphasis given to 'heat summation' meant Breuer's monopole site Rauenthaler Nonnenberg, which lies at higher and therefore cooler altitude, was excluded as not worthy of classification – whereas around three quarters of the vineyards in the Rheingau were included. Officially, this legally sanctioned version of Erstes Gewächse came into being with the 1999 vintage. This meant that Breuer, a leading light and one of the most important founding fathers of the classification, resigned from the VDP in protest and henceforth renounced the designation Erstes Gewächs for all his classified sites in Rüdesheim.

Twenty years of adaptation

In the 20 years since 1999, the initial classification has undergone repeated modifications. The Erstes Gewächs has become Grosses Gewächs throughout Germany, and the VDP model that currently sets the tone is ultimately a return to the idea that Bürklin-Wolf had in mind as early as 1994 with their internal additions 'G.C.' and 'P.C.'. Today Grosse Lagen (i.e. great growth or grand cru sites) rank higher than Erste Lagen (first growth or premier cru sites) and these in turn above local and estate wines. Over the years, however, the classification has repeatedly struggled with problems of logical coherence. One of its birth defects is that it was not market-led and, at the same time, was spread across German growing regions with completely different wine styles and grape varieties. What mades sense for the Mosel does not necessarily make sense in Baden.

The Mosel, for example — famous for its residually sweet and botrytised wines — initially had a hard time with the idea of defining a dry prestige wine at all. A further problem has not yet been satisfactorily resolved either: the strange concept of "site consumption" whereby an estate can only use the name of a vineyard site for one wine. This problem begins with an innocuous-sounding regulation: A Grosse Gewächs is, by definition, a single dry wine made from a site classified as Grosse Lage. The stumbling block for many wineries, especially larger ones, is that the vineyard name cannot then be applied to other dry wines from the same site: for example, there cannot be another dry Silvaner from the Stein vineyard in addition to Würzburger Stein Silvaner GG. Any such additional vinifications, perhaps intentionally kept in a less concentrated/more affordable style, must be downgraded to Würzburger Ortswein (village wine), even if the grapes come from the classified Grosse Lage vineyard.

Meanwhile, the VDP Rheinhessen is concerned about a different problem. In order to lend more esteem to the Ortswein category, it recently introduced the category Ortswein aus Ersten Lagen, which not only sounds confusing, but also suffers from the fact that the VDP Rheinhessen has not defined any Erste Lagen in its internal classification.

In other wine regions there is the problem that vineyards with a large surface area can be so heterogenous in terms of soil and mesoclimate that the designation of Grosse Lage necessitates the division of the site into individual parcels, called Gewanne. The rest of the site then becomes an Erste Lage in the VDP nomenclature. If the existing vineyard register of place names (the official land registry) does not have a suitable name for the Grosse Lage sub-parcels (or if the wine inspectorate has objections), this can lead to the bizarre situation that a fantasy name is given to the Grosse Gewächs wine, while the recognised site name is designated at a lower quality level.

"One could see it as a construction error that the VDP started the classification at the top. The Erste Lage as an intermediate level between village wine and Grosses Gewächs was only introduced afterwards," says Armin Diel, a winegrower and long-time VDP board member, who has significantly contributed to the classification. Diel also points out, however, that in the early years a certain amount of force was needed to get the idea of classification into the heads of the industry and wine connoisseurs in the first place. "But from today's point of view, it would probably have been better if we had said: first we will designate premiers crus, then we will develop the grands crus from them."

A world success

It would certainly be too much to expect that a classification such as the VDP began in the 1990s would mature into perfection over two or three decades. But nonetheless, the category of Grosse Gewächse is "a global success," notes Armin Diel, taking stock. The figures prove him right: in 2020, the 200 VDP estates sold almost two million bottles of GGs. There is hardly a winegrower who has not benefited from the classification. Some estates only produce a small amount of GGs and use the few hundred bottles as a banner to raise the prestige of their winery. A large winery like Robert Weil produces 30,000 bottles from its GG vineyard, Gräfenberg. Dieter Greiner of the Hessische Staatsweingüter, which is particularly richly blessed with great sites, is cagey about production quantities, but emphasises that the GG has "gained enormously in importance, especially in recent years".

And there are medium-sized wineries that have specialised in the production of GGs. Konrad Salwey, for example, the Pinot expert from Baden's Kaiserstuhl sub-region, scrolls through his accounts and reads out for 2020: "30,644 bottles". He goes on to report that his Pinot Noir GGs are now sold in Belgium — a market that traditionally looks to Burgundy for Pinot Noir and buys the best of the best there. There is no doubt that Grosse Gewächse from Germany have already achieved a lot in reviving the fortunes of the country's greatest vineyards, yet its global success story has only just begun.