Wine Blends: In Praise of Mongrels

Can a blended wine ever hope to compete with wine made from a single grape variety from a single parcel of land?

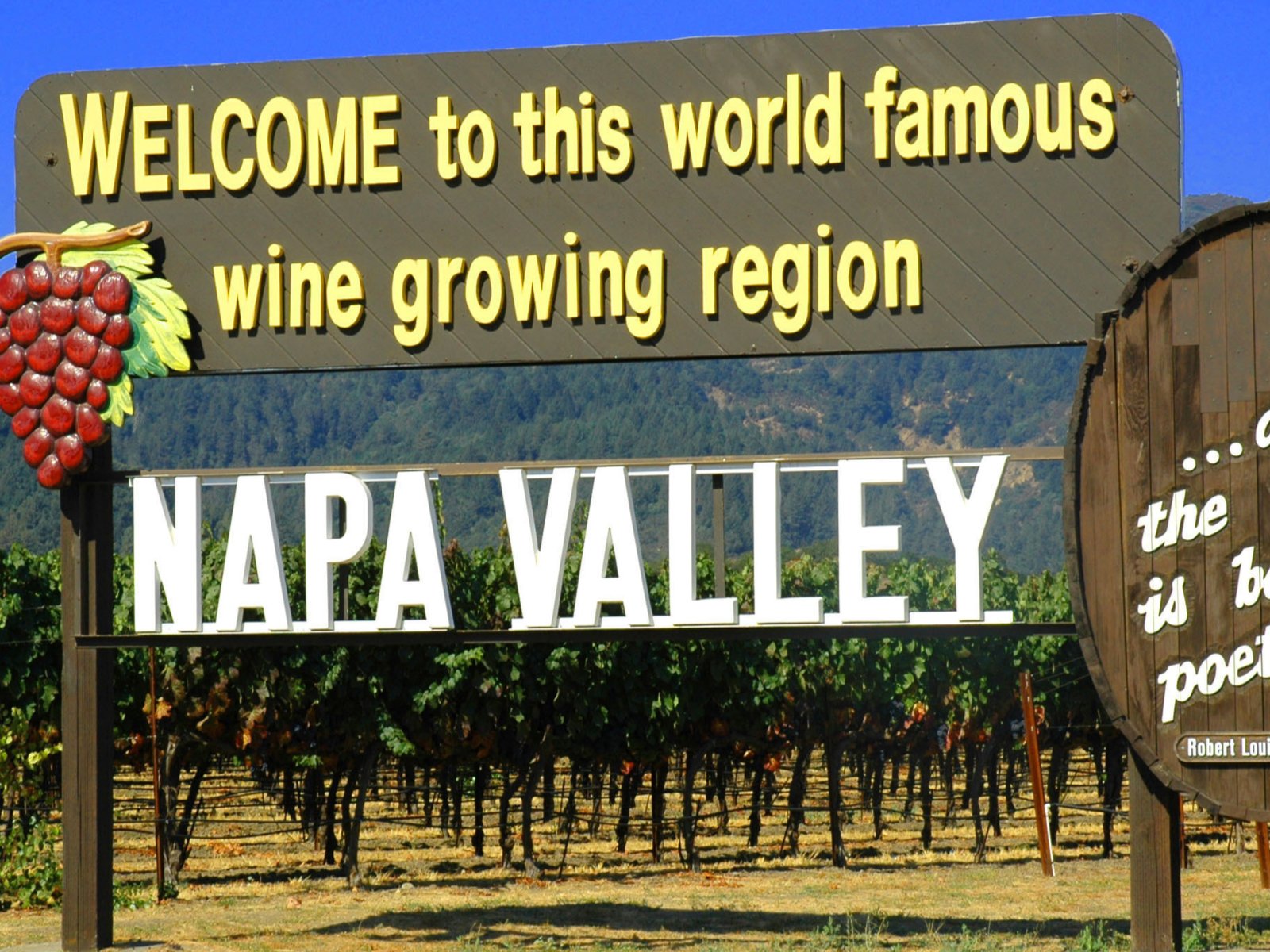

Are you a pedigree devotee? There’s an obvious, purist appeal to refining a breed’s characteristics in dogged pursuit of a perfect example. You see it in wine too: those producers who have dedicated generations of sweat and experience to creating the finest expression of a single grape from a single parcel of vines. Burgundy, the Mosel and Piedmont are prime examples of this approach, their disciples delighting in the ability of Pinot Noir, Riesling or Nebbiolo to transmit the character of a specific site. Unique and by necessity limited in volume, these are wines that attract high prices driven by their obsessive followers.

How can mongrels hope to compete with such greatness? That hybrid vigour can certainly result in great charisma, yes, but can a blend really ever hope to achieve the same level of nobility as its single variety, single site counterparts? Well, it depends how tenaciously you cling to that favourite but misleading producer mantra: “wine is made in the vineyards”.

As any chef will confirm, the quality of your raw materials is certainly a vital starting point. But equally, it is the chef’s creative and scientific genius that takes those ingredients to another level. In the world of wine, that task falls to the winemaker. If that wine is a blend, particularly one of the world’s greatest, most complex blends, then the winemaker’s role becomes akin to that of a top parfumier.

Bordeaux offers a prime, if relatively simplified, example of the art of the blend. Top producers here typically work with four grape varieties, each grown on a slightly different site and performing slightly differently from year to year. On top of that comes the decision of whether to create a blend that will shine early, when critics are forming their crucial initial opinion, or blossom in 20 years’ time, when wine lovers broach their bottle for a special occasion. What if the winemaker’s preferred blend marks a departure from the château’s perceived house style? These are thorny questions that tend to spark evasive answers.

Bordeaux blends are positively straightforward compared to the fiendishly complex array of components faced by a chef de cave in Champagne. Few houses here, especially among the biggest names, grow all their own fruit. Instead they must source their three main grape varieties – Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier – from hundreds of small growers scattered across 319 villages in four main sub-regions.

As if that were not complicated enough, the non-vintage style responsible for the vast majority of Champagne’s production requires the incorporation of reserve wine from previous harvests. Then factor in not only that NV must stay true to the house style year in year out, regardless of weather, but also that such consistency must be replicated across several million bottles. Next time you enjoy a glass of Louis Roederer, take a moment to admire the fact that up to 600 different wines may have contributed to the final blend.

Blending doesn’t necessarily just take place in the cellar. Most producers these days have indeed streamlined viticulture so that one parcel of vines features a single grape variety. These can then be vinified separately before being carefully combined into the final blend. But that level of control goes out the window with styles such as Austria’s Wiener Gemischter Satz or the Douro’s port. Here the tradition of a “field blend” still runs strong; indeed, it is actually stipulated in Wiener Gemischter Satz appellation laws.

For today’s oenology school graduates, trained to apply treatments and harvest at specific stages of a grape’s development, the field blend’s mix of late ripening and early ripening varieties is anathema. Consider though, the counter-argument that this mélange of different ripeness levels can even each other out and create a wine with more interesting personality.

What’s more, co-fermentation can bind the different elements contributed by each variety, whether it be colour, aroma, flavour, structure or texture, into a more stable, harmonious whole. Field blend advocates also maintain that, by preventing any single variety from dominating, it allows a clearer expression of the terroir. Isn’t that supposed to be what it’s all about?