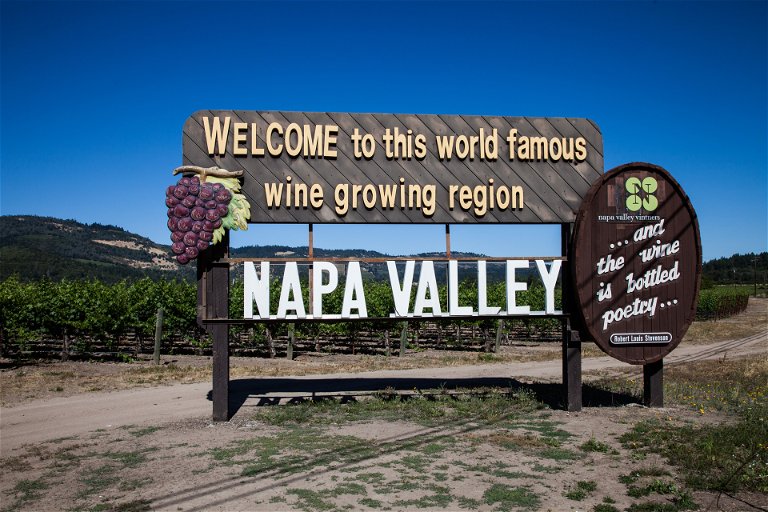

Californian Wine: Past, Present, Future

Many of the world’s top-rated red wines hail from California. They are rare and expensive – so what gives these wines their unique identity and where they are heading next?

Californian red wine, especially from Napa Valley, has a certain image. The wines are thought of as big, bold, sometimes even brash – and sinfully expensive. But while they undoubtedly speak of Californian sunshine, they come with more nuance than they are given credit for. They are joined by equally expressive reds from Sonoma and the Central Coast. The winemakers and estates may not look back at centuries of tradition, but they are at the cutting edge of winemaking. Because their wines are valued in the market, they can afford to lavish care on vineyards, invest in progress and attract talent. They are also dealing with a changing climate and are reassessing what it means to make wine in California – in all their numerous styles and philosophies. We are here to trace what makes these wines so unmistakeably Californian – because authenticity and sense of place are the cornerstones of fine wine. We find much to discover and rediscover in the Golden State.

The place and its past

California’s coastline spans 1,350km– longer than Italy’s boot. Its wine country covers just over eight degrees of latitude from its southernmost point in San Diego to its northernmost outpost on Lake Trinity. Then there is the crucial influence of the cold Pacific Ocean and its climatic interplay with the inland heat. In the numerous valleys along the coast and inland where both these elements are moderated by topography, read mountain ranges and their varying altitudes, vines thrive. That this land was destined for viticulture was as evident to Spanish missionaries in the 18th century as to the scores of European immigrants who arrived in the 19th century.

By the turn of the 20th century, there was a thriving and professional Californian wine industry: in the late 1850s there were 2,407ha of vines in California, by 1914, that had swelled to 121,114ha. Then came Prohibition. Ratified in 1919, the Volstead Act came into force in 1920 and was not repealed until 1933. After this disruptive blow, new pioneers emerged who set the course. André T chelistcheff in the 1940s and 50s, Robert Mondavi and Paul Draper in the 1960s, Warren Winiarski, Jess Jackson and many more in the 1970s and 80s.

Paris, Parker & cult wines

A turning point came in 1976, when the late British merchant Steven Spurrier staged a comparative blind tasting in his Paris wine shop, pitting the best French wines against a range of then unknown Californian wines. To their horror, famous French critics scored the Californian wines higher than their homegrown classics. The story was covered by Time magazine and all of a sudden California was no longer an arriviste – it had arrived.

At the time, California was still planted to a wide mix of grape varieties – suited to the land or not. But the ‘Judgement of Paris’, as it became known, along with another key figure, changed the California wine industry: an American critic called Robert Parker. His rise in the 1980s coincided with California’s – and his love for ripe, opulent wines soon made itself felt. A third element was also decisive: many vineyards had been planted on rootstocks that were not resistant to the phylloxera pest, thus when vineyards had to be replanted in the 1980s, more often than not they were planted to Cabernet Sauvignon.

In the 1990s, the phenomenon of the cult wine was born: fine wines, usually Cabernet Sauvignon-based, made in tiny quantities and initially released at expensive but still affordable prices, received top scores and sold out immediately. You were either one of the lucky early subscribers or had to languish on a waiting list for years. Prices went into the stratosphere, many jumped on the bandwagon and California gained its reputation.

California today

Today, the long shadow cast by the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s is waning and California, in tune with global viticulture, has turned its attention back to its soils, its land, its territory. The top winemakers strive to express place – that amalgam of site, climate, aspect, soil and culture – and the wines reflect their origin.

Some winemakers, in fact, have never done anything else. “There have been many turning points in Napa Valley’s history and in ours. I think one of the biggest ones, in terms of wine quality, was when the focus shifted from the cellar to the vineyard. Here at Shafer that started happening in the late 1980s and has continued to evolve every year,” says Doug Shafer of Shafer Vineyards. “We farm over 200 acres and we’re out there just about nonstop from January through November – someone comes in contact with each vine at least 11 or 12 times. The number of times human hands come in contact with Shafer vines each year is more than 2.7 million.” He notes how it took a while to recognise what would work best: “The grape that really shines on our site is Cabernet Sauvignon and that’s the result of a lot of trial and error. Early in our history this property has been planted to Zinfandel, Merlot, Chenin Blanc, Sangiovese, and Chardonnay. The clear winner is Cabernet Sauvignon.”

Valley and mountain

Cathy Corison is another winemaker whose focus never swayed from her vines. She founded her estate in 1987 in Napa’s Rutherford AVA (American Viticultural Area) after working as a winemaker across the Valley. She explains why Rutherford, on an alluvial fan that straddles several AVAs, is special: “Extremely well-drained gravelly loam soils hold water for the vines when they need to grow in the spring. Thanks to rainless summers, they dry out right at veraison, when the grapes change colour, so the vines get busy ripening their fruit.” It is on this land that her real treasure stands: “Kronos Vineyard is situated on the bench with soils so gravelly that we could mine them for gravel,” she says. “The hottest part of the valley, St. Helena, has the perfect climate for Cabernet with the heat to consistently and optimally ripen the fruit, retain acidity and lignify seeds.

“Kronos is also one of the last old Cabernet vineyards in the Napa Valley, planted in 1971. Growing on St. George rootstock it avoided the fate of most other vineyards that were on AxR1 rootstock when phylloxera came back. Yields are pitifully low, but it has been a gift to work with these gnarly old ladies. The scraggly clusters of tiny berries result in wines of remarkable concentration. Kronos has been farmed organically for over 25 years, long before it became fashionable, so its soils are wildly alive.”

Another historic vineyard on the Valley floor is To Kalon, first planted in 1868, its Greek name meaning “highest beauty.” The late Robert Mondavi (1913–2008), one of the key figures in forging quality viticulture in Napa Valley, had made wine from parcels of To Kalon from the 1960s onwards. Owned by Constellation Brands today, the Mondavi brand is still going strong. Geneviève Janssens, chief winemaker at Robert Mondavi Winery, trained with the man himself and says: “Robert Mondavi knew that he had a treasure in To Kalon. It offers three important things: personality, resilience and a source of inspiration. Its beauty is also its resilience: whatever the vintage conditions, we always end up with great wine.

“It was this passion and Mondavi’s pursuit of perfection at his winery that inspired so many to follow in his foot steps.” One of those he inspired was Bill Harlan. He founded his eponymous estate in 1984 in the hills above Oakville. While Kronos and To Kalon speak of the Valley floor, others make different styles on the mountains that rise on either side of the Valley. Harlan is one of them. He delibera tely went for hillside vineyards. Harlan’s Proprietary Red became one of Napa’s most soughtafter wines, grown at 100 -167m, renowned for its structure and longevity. Before buying the land for the original Harlan Estate, Harlan had eyed another property which finally came up for sale in 2008. This is the family’s Promontory Estate, and again, the wine is different from Harlan – because it is grown in very different conditions – despite being just 500m apart. Surrounded on all sides by woodland, winemaker David Cilli describes the land as “wild, very steep, rugged, untamed.” It lies along a geological faultline between two ridges on metamor phic rock. Motion sensor cameras have captured mountain lions and bears on the land. The wine is distinct from Harlan: where Harlan is velvet, Promontory is silk. Cilli says the surrounding forests “harvest the fog and moisture of the mornings and release it later in the day,” lending freshness to the wines. “Freshness is the opposite of gravity in the mouth, it gives you that tonic feel.” Today, freshness is as prized as power and even those who know Napa will find something new to discover – with a different style. “We feel there is a step change in Napa, too,” Cilli says.

When Ann Colgin founded her estate in 1992, she also looked for mountain vineyards. Paul Roberts MS, president of Colgin Cellars, explains that the three single vineyard sites they farm are very different, resulting in distinct styles of wine: the historic Tychson Hill vineyard at 91-129m is on a rare volcanic formation, sitting between Spring Mountain and Diamond Mountain. It is their hottest site during the day and the coldest at night, creating exquisitely elegant wine. The Cariad vineyard on Spring Mountain at 122-152m is on an ancient riverbed uplifted by geological movement and benefits from the cold air flows of Spring Mountain; the IX Estate vineyard, the highest site at 335-427m is also of volcanic origin, “a lava flow with iron-tinged red clay. Mixed with the rocky base material it adds a sanguine nature to the site,” Roberts says. Likewise, the four wines of Lokoya from Spring Mountain, Diamond Mountain, Howell Mountain and Mount Veeder are distinct and straight 100% Cabernet Sauvignon expressions of these sites, fermented with native yeast and bottled unfiltered to underscore these differences.

The only way is up

But plush red wine is not just the preserve of Napa Valley. To its northwest, across the Mayacamas Mountains, in Sonoma County, there are less well-known but similarly compelling AVAs – at higher elevations. Vineyards in Alexander Valley, Bennett Valley and Knight Valley start at elevations of 150m/500ft and rise much higher.

Altitude makes a difference because the fog layer that comes in from the Pacific burns off earlier, allowing more sunlight, while cooler temperatures mean a longer growing season. When the late Jess Jackson (1930-2011), the man behind the famous Kendall-Jackson brand, wanted to create a red wine to rival the world, he lured French winemaker Pierre Seillan to California and gave him the pick of his Sonoma vineyards. Seillan chose sites in these high-elevation AVAs. This is how Vérité was born in 1998. Three wines are made: Merlot-based La Muse, Cabernet Franc-based Le Désir and Cabernet Sauvignon-based La Joie. Seillan’s blends are created from what he calls “micro-crus” and he says: “My only goal for Vérité wines was – and still is – to capture the best message of the soils from my different micro-crus to elevate the Sonoma appellation to the highest level in the world, with the unique style and signature of Vérité.” His wines are yet another facet of California – different, elegant, distinct.

Down the coast

The trail of fine red wine continues right down the coast. Just south of San Francisco, the Santa Cruz Mountains AVA is home to another Californian Cabernet icon: Ridge Vineyards’ Monte Bello. The Monte Bello Vineyard was first planted in 1862. In 1949 it was replanted to Cabernet Sauvignon and in 1962 the first Ridge Monte Bello wine was released. In 1969 the philosophy graduate Paul Draper joined as winemaker and took the estate to ever greater heights. Harvest at this elevated vineyard at 600m/2,000ft is not until October. This is one of California’s inherent contradictions: further south is not necessarily warmer as the Pacific and altitude always have a role to play. John Olney is now the head winemaker. He says: “The combination of a coastal, cool climate and limestone-rich soils is rarely seen in California. This allows the grapes to attain full ripeness without excessive sugar, retaining firm, natural acidity. Since Monte Bello is all mountain-grown fruit, soil fertility is modest, resulting in lower yields and incredible concentration. Tasting the wine is almost like tasting the mountain itself.”

With its high proportion of American oak in winemaking, expressed in rich tones of coconut and vanilla which suits the ripe but defined fruit, Monte Bello is unmistakably and unapologetically Californian.

Three hours further south, Paso Robles, is another hot spot for full-bodied reds. Again, there are distinguishing features that make the area suited for world-class wines. Tablas Creek is a French-American co-production. The late Robert Haas (1927-2018) was an importer of French wines and partnered with the Perrin family of Château Beaucastel in the Rhône Valley, France, to create Tablas Creek. They hit on the Adelaida District of Paso Robles because of the area’s calcareous soils – and the altitudes of 427 - 487m/1,400 - 1,600ft. Robert’s son Jason now runs the winery. “What I taste in Paso Robles is purity of fruit from 320 days of sun, vibrancy of the acids preserved by our altitude and our cold nights,” he says, “and a salty, sea-spray minerality from the chalky soils here.” Haas’ top wine, Esprit de Tablas, is a blend of Mourvèdre, Grenache, Syrah and Counoise – different from the plush Cabernets, but definitely top range – with a spicy allure.

Daniel Daou of Daou Vineyards is just down the road but has specialised in Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay. He also emphasises the calcareous soils of the area: “They provide minerality and freshness that allow for dry-farming or deficit irrigation and wines made naturally without acidification.” He also points to the altitude of 670m/2,200ft and the proximity of the Pacific which is just 22km/14 miles away. “This allows us to have a climate warmer than Bordeaux and cooler than St. Helena in Napa.”

His wines have a different kind of texture and real brightness. He observes that the elegant and cooler style of his wines resonates with drinkers – despite the supposed “heresy” of planting Cabernet Sauvignon in Paso Robles.

"What I taste in paso robles is purity of fruit from 320 days of sun and vibrancy of acids preserved by our altitude," said Anne Krebiehl MW.

Feeling the heat

The challenges of climate change are real – as are the attendant extreme weather events and wildfires. While the cold Pacific acts as an air-conditioning unit for coastal vineyards, inland areas are feeling the heat. Ridge Vineyards’ John Olney says: “Especially in the era of climate change, starting with grapes that are in equilibrium is a big advantage.” Across California, there are a range of sustainability programmes, like Napa Green. The uptake is big – by 2019, 99 percent of Sonoma County vineyards and 94 percent of Napa vineyards were certified sustainable. Across the state, 55 percent of vineyard acreage is certified sustainable – so water preservation and soil protection is an ever-present endeavour.

But climate change also makes itself felt in other ways. Colgin’s Paul Roberts says much more attention is now paid to water use and thus, the proportion of Merlot in the Colgin blends has steadily decreased over the years. “Merlot loves water like a kid loves candy,” he says about the vines’ thirst. He also underlines how aware everyone is of preserving freshness: “We talk about breeze and airflow, but for different reasons than in European viticulture. For us, it is to add freshness, preserve perfume and heighten acidity by cooling a vineyard down.” He notes that statewide, including areas that do not produce any wine at all, 2021 was the hottest year on record; he also adds that in the past decade, there has always been “some form of drought.”

While some estates question whether Cabernet Sauvignon will still be the right answer for California in the coming decades, Roberts takes a long-term view, informed by historic perspective: “Over the next 30 years, in a generation, will we have to plant Touriga Nacional [a heat and drought-resi- stant grape from Portugal]? Maybe. As our climate continues to evolve, we will continue to make that evolution, too. In agriculture you cannot be revolutionary.” Style is changing, too: “We are able to make natural wines that retain elegance and freshness and don’t sacrifice power for elegance, the consumer adoption has started to shift in the US and in California,” says Daniel Daou.

In the meantime, Californian winemakers must also ensure they can compete with marijuana growers for farm labour now that recreational use of the plant has been legalised. Another challenge is attracting new drinkers – appealing to a younger demographic is hard with the current price tags. Nonetheless, the fact that Californian reds, especially blue-chip Cabernets, are seen as a worthwhile investment was proved again in February 2022 with the $250 million sale of Shafer Vineyards to a Korean investor. Doug Shafer knows that wine is essentially about agriculture and all its inherent challenges: “Anyone who wants an easy, predictable life should definitely avoid farming,” he says. Winemakers the world over will agree – and also on the fact that Californian wines can rival the world.

California: A perspective

Katie Lazar and Christopher Howell, both 70 years old, have lived at Cain Vineyard & Winery on Spring Mountain in Napa Valley for years and Howell has made wine for the past 30 vintages there. In September 2020, they narrowly escaped the Glass Fire that raged through Napa County for days. They lost their home and some vineyards to the fire. After so many years, and this great loss, Howell has some perspective on the evolution of Napa Valley – and thus California. He is wondering what to replant.

“Places like the Napa Valley might be likened to the growing up of a person. At first, as

a young child, we are full of potential, and certain proclivities might declare themselves, but it is really too soon to know what is possible. This might have been the case of Napa Valley in the 1870s and 1880s and again in the 1940s to 1960s. In these periods, the range of grape varieties planted and the wines made covered virtually the entire gamut of known wines.

Then, as an adolescent, we begin to try on various identities, but it is too soon to be even aware that what we are doing is trying to find ourselves. This might be where we were in the Napa Valley during the 1970s, 80s and early 90s, as we incessantly tried to compare our wines with the great wines of the world. At that time, our focus had narrowed to fewer varieties – especially Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon. But, as with all adolescents, this still didn’t mean that we knew what we were doing.

As a young adult, the Napa Valley is still struggling. We are just beginning to emerge from the fog of Cabernet and new oak barrels, but there is cause to hope that we are beginning to understand our terroir and our identity as a red winegrowing region.”