Large Bottles: Is Bigger Really Better?

Large format wine bottles have near mythological status, especially in Bordeaux and Champagne. Falstaff went digging to get to the bottom of some of the legends.

A heaven full of large bottles welcomes the guests of the famous Arlberg Hospiz hotel in St. Christoph in the Austrian Tyrol. Dozens of these treasures made of glass and containing the juice of fermented grapes are mounted on the ceiling in the cellar of the legendary Adi Werner. Their contents, in turn, transport guests to heaven; for bottles that contain several times the volume of a normal 0.75-litre bouteille are surrounded by the aura of the exclusive. A large bottle is always a rarity per se. The volume of the bottles ensures that the wines mature more slowly and taste more complex – that is the reason why the effort is made with giant bottles in the first place.

Yet these magnum bottles, double magnums, imperial and even larger formats are also surrounded by some mystery. What exactly is the historical origin of these bottle sizes? And why do the formats all have biblical names? Is it possible to calculate how much longer a wine in a large bottle needs until it is ready to drink? And is it true that the best barrels are used to fill large bottles? Falstaff got to the bottom of all these questions and came up with some surprising findings.

A history with many twists and turns

There is much to suggest that the first large bottles came into being in Ancien Régime prior to the French Revolution. As early as 1725, the name Jéroboam seems to have been common in Bordeaux for a particularly large glass bottle. Presumably, this name was chosen at the time to express the luxury associated with such a bottle. After all, the biblical Jeroboam had two costly temples built and furnished with golden calves for worship. Once this example was set, people later simply used other characters from the Old Testament to give names to various other greats: Rehoboam, Salmanazar, Nebuchadnezzar, and so on.

The large bottle seems to have been a significant qualitative advance at a time when most wine was still stored and traded in barrels – especially since it was discovered around the same time that the bark of the cork oak was ideally suited to making bottles water-tight and safe for transport.

Adi Werner remembers being shown magnums dating back to the 19th century by Thierry Manoncourt at Château Figeac at the end of the 1970s. Manoncourt told him that since the beginning of the 19th century it had been customary to bottle magnums for the Russian Tsar. "At the great festivities that the Tsar celebrated in St. Petersburg, high nobility came from all over Europe; after all, the Russian court was related to almost all of them. And at these celebrations it was of course great when the servants could walk through the hall with a giant bottle on their shoulder and 80 guests were poured from one and the same bottle," says Werner.

Around 1880, the first large bottles appeared in Champagne, according to Brigitte Batonnet from the Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne. Why this was done at that time is unclear, Batonnet suspects: for promotional reasons. It is quite possible, however, that the nobility devoted to champagne played a role here as well. The time period corresponds amazingly closely with the oldest magnum bottle, which Château Haut-Brion, for example, has in its own cellar: Cécile Riffaud of Château Haut-Brion reports that the filling of magnums seems to have become more common only in the 1920s. The oldest double magnum dates from 1929, the oldest Jeroboam from 1952, the oldest Imperial from 1945.

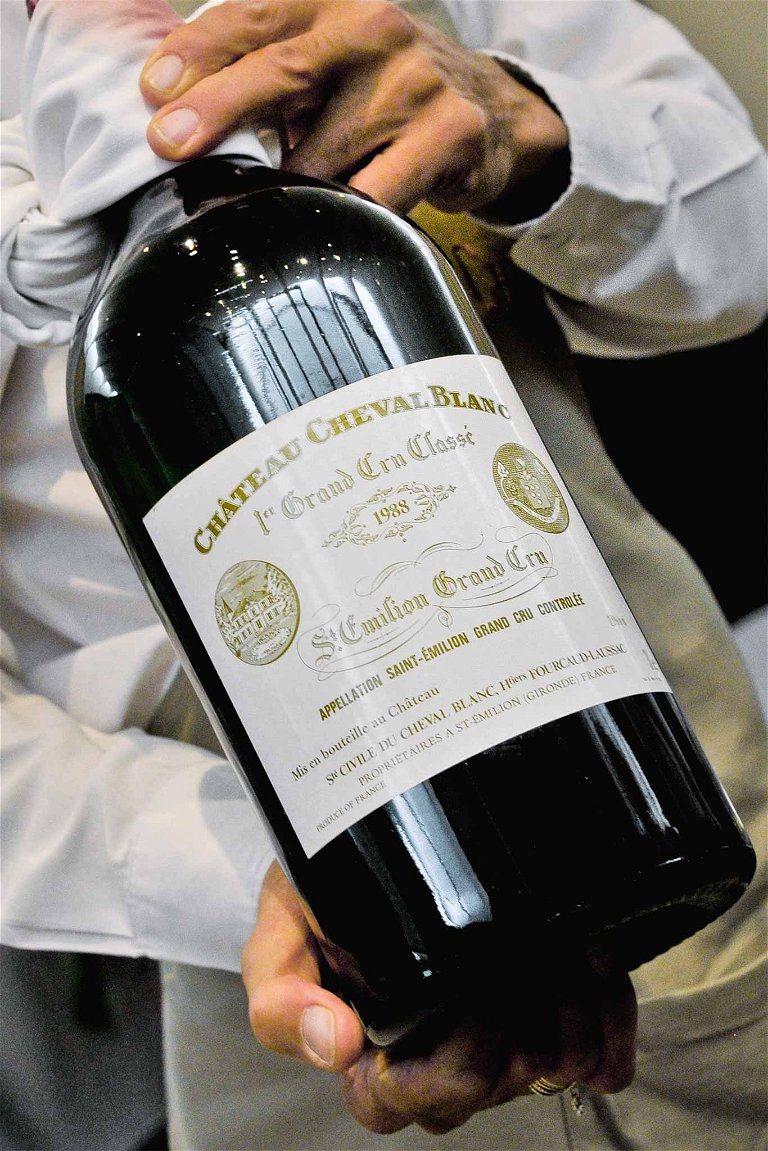

At Château Cheval Blanc, the oldest magnum still in existence dates back to 1920 and is also a château bottling. "A look at the stocks shows," says commercial director Arnaud de Laforcade, "that at that time the winery only put aside magnums and double magnums in particularly good vintages; it was only after the war that the production of large bottles became more systematic."

Jean-Michel Cazes of Château Lynch-Bages points out that until the 1970s, the vast majority of Bordeaux wines were bottled by merchants, and whether or not large bottles were produced was at the discretion of the merchants and their customers. "But the demand must have been low and the quantities limited," says Cazes. "Of course, there were a few magnums and large formats among the small portion of wines that were bottled at the château even back then. But even there, very little was produced, almost only for their private cellar. Sometimes a wine merchant would order magnums at the château and then change his mind at the time of delivery. Then we would deliver him normal bottles and end up with a small stock of magnums that we could sell later. This happened sometimes, but quite rarely."

From Champagne, Michel Drappier points out the problems that bottle fermentation can cause in the large bottles: "My grandfather produced only normal-sized bottles, my father made magnums – and I started transferring the champagnes fermented in single-quart bottles to larger formats in the eighties. But because we have a low sulphur content, there was always a risk of oxidation when transferring to larger formats. So in 1989 I decided to do bottle fermentation in all sizes. The first attempts were a failure because the Methusalems, Balthasars etc. were not designed to withstand the pressure of secondary fermentation. I remember losing 40 percent of my first Tirage Methusalem and my father was quite angry. Today we use stronger bottles so the loss is acceptable, even if it is much higher than standard bottles."

Burgundy, Piedmont, Port

Bordeaux and Champagne are the only regions where large formats have been regularly in use for some time. For Burgundy and the house of Bouchard Père & Fils, Céline Livera reports that the use of large bottles is still a comparatively new phenomenon. "In our cellar we still find some magnums or jeroboam from the forties, fifties, sixties and seventies, but only very few and only from sites we own, such as Vigne de l'Enfant Jésus or Le Corton." However, it is common in Burgundy for winemakers to bottle wines in Methuselah or Jeroboam formats in anticipation of an upcoming family event such as a wedding or anniversary, especially if the vintage has been good.

In Piedmont, Camilla Fontana of bottle manufacturer Albeisa reports that the five-litre format is more typical than three-litre bottles, and there is also a 12.5-litre format called Quarto di Brenta. The Brenta used to be a hollow measure (about 55 litres) common in the Turin area. At Giacomo Conterno, Stephanie Flou says, their Barolo Monfortino 1955, for example, was bottled in the Quarto di Brenta format, "sometimes these large bottles were at the request of individual customers, but unfortunately we do not have more precise records".

The Douro Valley also has its own large bottle for bottling port wine, the Tappit Hen (bonnet hen), a squat shape with a capacity of 2.25 litres (previously also 2.1 litres). The historical origin of the Tappit Hen is a pewter jug of the same name with a hinged lid, which used to serve as a measuring or transport vessel. In the port houses of the Symington family (Graham's, Dow's), this bottle size is still used today.

Does a magnum contain a different wine?

One of the most persistent legends surrounding magnum bottles is the claim that only the best barrels are used for their bottling. While there seems to be a reason why this legend arose, it nevertheless does not correspond with the truth. "With absolute certainty," writes Cécile Riffaud of Château Haut-Brion, for example, "we can confirm that there have never been extra barriques for bottling magnums." Jean Michel Cazes gives an identical answer: "As far as special barrels for large sizes are concerned, this is pure legend."

But Cazes also has a clue as to how the legend could have come about: "What is true, on the other hand, is that the work in the cellar used to be much less efficient and precise than it is today, and also slower. Bottling took a long time, sometimes several weeks or even months between individual bottlings, depending on the priorities of the vineyard work. This led to variations in quality and the famous "bottle variation". Sometimes wines that were bottled later were even subjected to an additional soutirage (racking)."

Is there a rule of thumb?

All experts agree that wine matures more slowly in large bottles. The reason is easy to see: The ratio of wine volume to oxygen contact area shifts more and more towards the wine the larger the bottle becomes. Nevertheless, it is difficult to come up with a universally valid formula, as wines and vintages differ too much in their characteristics. Stefan Schachner, sommelier and proven large-bottle connoisseur from Hotel Gupf in Rehetobel, Switzerland says: "For every three litres, you can calculate five additional years until the wine reaches drinking maturity." But he also qualifies: "Beyond six litres, the calculation becomes difficult. We recently opened a ten-year-old 18-litre bottle that tasted like it had just been filled. It's as if the wines stop their development."

Adi Werner gives as a guideline that a 750ml Bordeaux from a good year needs eight to ten years to reach drinking maturity and then remains at its peak for 15 years. "In the magnum, it takes twelve to 15 years to reach drinking maturity, and in the double magnum another 20 percent or so longer."

We asked technically oriented oenologist, Mireia Torres, who bottles single-vineyard wines in large formats at the Jean León winery: In her opinion, wines with low pH values (i.e. healthy acids) benefit disproportionately from the slower maturation. A bonus for Rieslings in magnum bottles, for example!

Sommelier Stéphane Gass, sommelier at the three-star restaurant Traube Tonbach in the Black Forest, cites similar figures to Schachner and Werner: "Seen over ten years, a magnum tastes about five years younger." However, Gass also points out that very large formats harbour potential for disappointment if they have been bottled by hand (or decanted from normal bottles). As a rule, the qualitative safety of machine bottling can only be guaranteed up to the three-litre size. His plea is for Champagnes in double magnums where bottle fermentation has taken place in the same vessel: "They can be sensational." In the case of still wines, Gass considers the magnum to be the "perfect size"; even a Marie-Jeanne (2.25 litres) from Château Cheval Blanc 1953, which he once tasted, was exceptional.

Guests who like to drink

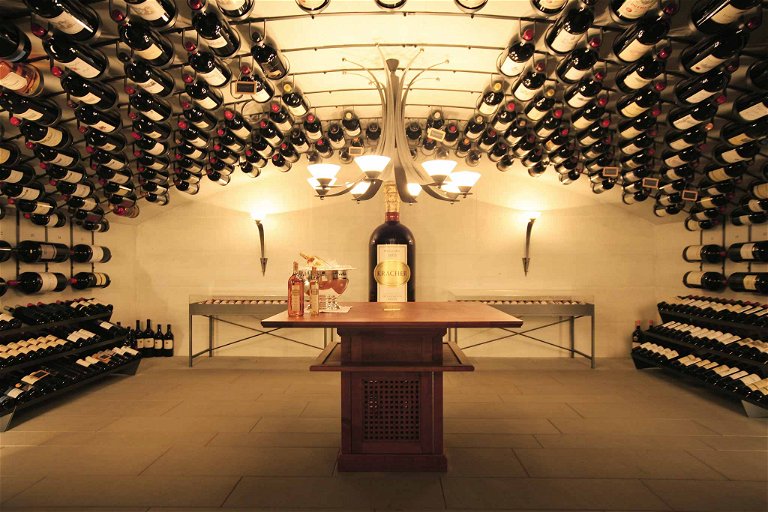

At Hotel Gupf, on the other hand, "we don't even count the magnum format among the large bottles", sommelier Stefan Schachner muses. 800 large bottles beyond the magnum are stored in the cellar, including a unique specimen with a capacity of 480 – in words: four hundred and eighty – litres: a 2007 Trockenbeerenauslese by Alois Kracher. Opening this two-metre bottle is not imminent and has been forbidden by owner, Migg Eberle, but other formats are frequently ordered: "Magnum bottles go daily, and we also sell double magnums regularly." The previous record holder, says Schachner, was a table of 17 people who drank a 27-litre bottle at lunch. "And I even had to bring them some more!"

Adi Werner does not complain about the lack of demand for large formats either. As most of the 3,600 large-format bottles are currently stored in an external warehouse. Werner is building a new cellar, which should be ready in November 2022. "It will be a circular cellar, our wine team has come up with something spectacular," announces Werner, who points out that most guests at the Arlberg Hospiz sooner or later ask for a cellar tour. "Then Karl-Heinz Pale, our head sommelier, shows the treasures. And when he is then asked whether they also sell some of it, he says 'yes, of course'. We are not expensive either. If the bottle is not drunk in the restaurant, we often charge a wholesale price. Only if it's a very old bottle do we sell it – on the condition that we get a glass of it."

These are the different bottle sizes and the regions where they are most common.

Magnum - 1.5 litres

(2 bottles: Bordeaux, Champagne, Burgundy)

Marie-Jeanne - 2.25 litres

(3 bottles: Bordeaux)

Tappit Hen - 2.25 litres

(3 bottles: Port)

Jeroboam - 3 litres

(4 bottles: Champagne, Burgundy)

Jeroboam - 4.5 litres

(6 bottles: Bordeaux)

Rehoboam - 4.5 litres

(6 bottles: Champagne, Burgundy)

Methuselah - 6 litres

(8 bottles: Champagne, Burgundy)

Imperial - 6 litres

(8 bottles: Bordeaux)

Salmanazar - 9 litres

(12 bottles: Champagne, Burgundy)

Balthazar - 12 litres

(16 bottles: Champagne, Burgundy)

Nebuchadnezzar - 15 litres

(20 bottles; Champagne, Burgundy)

Goliath or Melchior - 18 litres

(24 bottles: Bordeaux, Champagne, Burgundy)

Solomon - 20 litres

(26.67 bottles: Champagne)

Sovereign - 25 litres

(33.33 bottles: Champagne)

Primat - 27 litres

(36 bottles: Champagne, Bordeaux)

Melchisedec or Midas - 30 litres

(40 bottles: Champagne)