The Magic of Making Cheese

Our resident cheese expert muses on the magical transformation from milk to cheese.

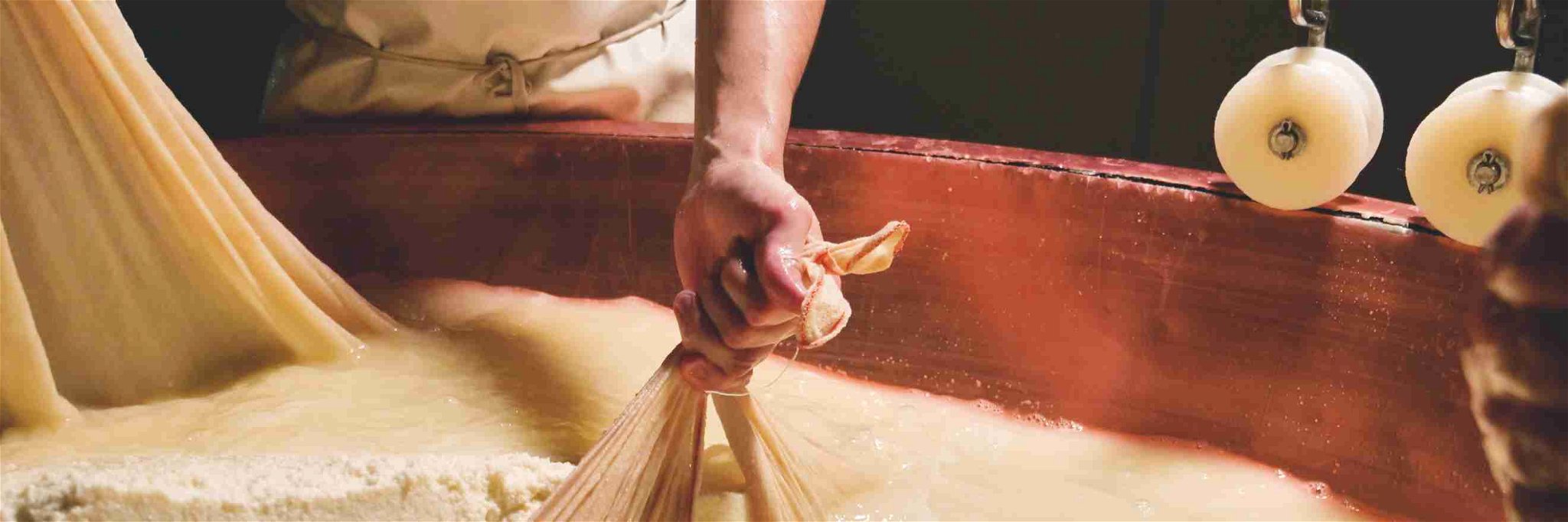

The closest I’ve ever got to doing practical magic was ladling curd into moulds on my friend Mary’s small farm in Somerset. It was a slow setting cheese and so we often ended up working around midnight, ladling scoops of snow-white curd into the cylindrical plastic moulds laid out in neat ranks on the steel draining table. In the quiet of the countryside the only sounds were the liquid trickle of the whey draining into buckets sitting on the red tiled floor, and the occasional hoot of an owl. Ladling requires slow precise movements and in that mystical atmosphere I felt as if I was participating in some ancient ritual.

Transformation

Adding to the sense of the miraculous was that the bland liquid milk that we had started with a day before had transformed into a gel-like curd with a zingy fresh acidity, and was well on its way to becoming cheese. Nowadays we have a scientific explanation for this process – the bacterial starter culture we added to the vat had acidified the milk by converting its lactose to lactic acid, creating that fresh, sour flavour, and the rennet we had added shortly after had coagulated it, hence the texture.

Goddesses and Curses

For most of the nine thousand years of dairying history, cheesemakers believed that goddesses, fairies, and the Christian God himself were behind the mystery of cheesemaking. In Britain and Ireland, an ancient Celtic goddess called Brigid oversaw dairy. Pre-Christian carvings from Hadrian’s Wall in the north to Gloucester in the south-west show her churning cream for butter and adding cream to a vat to make rich triple-cream cheese. Like many pagan figures, Brigid took to the new-fangled religion and Christian Irish cheesemakers would hang a magical cloth called St. Brigid’s mantle in their dairy to protect their cows from sickness and ensure a plentiful supply of milk.

In the godly dairies of 17th century England, when your milk failed to turn into curd it was a sign that you had been cursed by a local witch. The remedy was to stop making cheese and go to church. Next you needed to perform a ritual cleansing of the dairy and bring a rowan branch into the dairy - rowan was thought to ward off the evil eye.

Viral Spoilage

It seems that these wise dairywomen were on to something, since the most likely reason for this failure was the presence of phage, a troublesome virus that can develop a taste for a particular strain of starter culture [its name Bacteriophage literally means bacteria eater]. If phage eats your culture, nothing will happen to your milk. By stopping cheesemaking the cheesemakers were starving the phage, the vigorous clean got rid of most of the surviving virus, and the rowan branch might have brought in a new strain that any remaining phage wouldn’t recognise as food.

Instinct and Flavour

Today, even with our digital thermometers, acidometers and microbial testing regimes, a cheesemaker’s instinct is still as vital as it ever was, and to say of another that they ‘make their cheese by the clock’ would be a grievous insult. While modern science and dairying technology might have helped to make cheese a more consistent product, I’m sure it’s that instinct, and a little bit of magic that makes proper cheese taste so miraculously good.