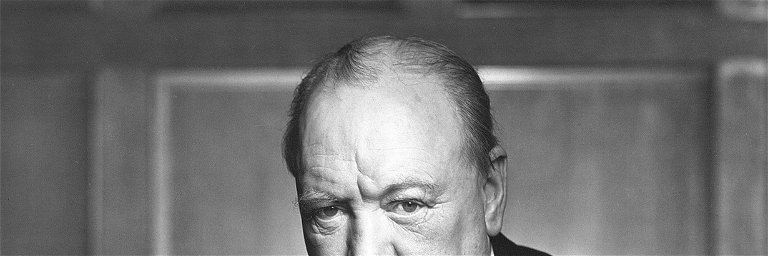

Why Winston Churchill hated mediocrity when it came to food and drink

Winston Churchill did not want to do without whisky and cigars any more than he wanted to do without exquisite food – every day.

On May 8, 1945 at 3pm, Winston Churchill announced the end of the Second World War. In his radio address, the British Prime Minister informed the nation of the unconditional surrender of the German Wehrmacht. He concluded his speech with “Nothing should prevent us from celebrating Victory Day in Europe today and tomorrow. Forward Britain! Long live freedom! God save the King.”

But before Churchill responded to his own call to celebrate the victory, he turned to his cook, Georgina Landemare, as it was immensely important for him to thank her “sincerely”, as he said, because: “Without you I would not have survived the war.” This was not only exceptional praise, but it was meant in deadly earnest, for eating and drinking well was essential to the stability and well-being of the statesman. “One should offer the body something good, so that the soul may desire to dwell in it,” was his conviction. And Georgina Landemare undoubtedly did Churchill’s body and soul good in those difficult times for everyone. It was her “war work” to cook and look after Churchill, his family and his many guests, she later explained. The robust British woman, who was married to the French chef of the noble London Ritz hotel, first entered the Churchills' kitchen in 1930.

From then on, Winston Churchill’s wife Clementine had always hired her for large invitations and receptions. The statesman held no political office at the time, so he devoted himself to his journalistic and literary work at his Chartwell country estate in southern England. But that alone was not enough for the busy man and several times a week, he and Clementine invited people to dinner parties at their home. He understood that these social gatherings were not only a pleasure, but rather an investment in his future: the perfectly planned dinners gave him the opportunity to confer with friends, win over rivals and get information, from diplomatic secrets and intrigues to gossip. In the process, his guests experienced him as an extremely friendly and generous host who offered unlimited Champagne, cigars and brandy – and who became more and more chipper the longer the evening lasted.

When the Second World War began and Churchill became Prime Minister in 1940, as well as Defence Secretary of the newly formed Coalition Government, Georgina Landemare offered her permanent services to the Churchills. Clementine did not hesitate for a minute and welcomed the cook to Number 10 Downing Street: “I knew she would make the most of the meagre wartime rations and satisfy everyone in our household.”

Georgina soon learned that it would be anything but easy to meet the demands of the master of the house, especially when it came to his culinary needs. His answer to the question of what he liked was: “My taste is simple. I am easily satisfied with the best.” And her dishes stood up to his discerning palate. She knew his culinary preferences as well as his dislikes. Churchill appreciated traditional English dishes like chicken and roast beef with Yorkshire pudding; kidney pie; beef tenderloin pie; or steaks. He preferred clear bouillons to cream soups, and if he had to choose between fish and shellfish, he chose the latter.

Churchill preferred to finish his dinner with cheese, however, he was not enthusiastic about Cheddar, the most popular cheese in the English kingdom; rather, the blue cheese Stilton and Swiss Gruyère were his favourites. The gourmet attached the greatest importance to the fact that cheese that came to his table was not bought just anywhere, but only at a particular fromagerie: “A gentleman only buys his cheese at Paxton & Whitfield,” he said. The traditional company still exists and has been one of the court suppliers of the British Royal Family for many years. Desserts such as puddings or tarts, on the other hand, were never high on Churchill’s culinary agenda.

Alcoholic beverages were at least as important as exquisite food for the sports refusenik. Whether port, brandy, sherry, Champagne or whisky – there was not a day on which Churchill wanted to do without these refreshments. Asked about his drinking habits, Churchill replied in old age: “All I can say is that I got more from alcohol than it got from me.” Whisky accompanied him from morning till night; even after his opulent breakfast, which he always ate in bed, he drank his first drink and smoked a cigar with it. He never drank whisky straight, but diluted it heavily with soda water and ice cubes. As a young soldier, he got into the habit of drinking this mixture during his missions in India and South Africa – since the drinking water in these countries was not clean, he was advised to dilute it with high-proof alcohol. He also ended his day with such a “mouthwash”, preferring Johnnie Walker Black Label to all other brands. Churchill even made an artistic monument to the drink.

In 1930, the passionate amateur painter created the oil painting ‘Jug With Bottles’, in which a bottle of Johnnie Walker Black Label can be seen alongside a bottle of brandy. Churchill would never have dreamed of the price this painting would one day fetch: in 2020, Sotheby's auctioned it off for £983,000 (approx. €1.1million) – the auction house had expected proceeds of around £300,000. The opulent politician also had a particular weakness for another drink: Champagne. “Even a single glass of Champagne gives one a feeling of elation,” he noted as early as 1898. And in his opinion, there were always opportunities to treat himself to a glass or two: “When you win, you deserve it; when you lose, you need it.”

Since Churchill did not want to be dependent on the attention of butlers at banquets, he always made sure to have a bottle of Champagne to himself. And by far his favourite was Pol Roger; the company is still family-owned today, and considered the politician’s loyalty a great honour, and when Churchill died on January 24, 1965 at the age of 91, it put a mourning ribbon on all deliveries to Great Britain and named one creation, Cuvée Sir Winston Churchill, in homage to its most famous customer.