Art & Taste: Giuseppe Verdi, Father of Grand Opera

Giuseppe Verdi suffered from being famous most of his adult life. At 37, the composer retired to his estate in Sant'Agata, Italy, where he enjoyed nature and down-to-earth food.

With the premiere of Nabucco, nothing was the same for Giuseppe Verdi. On March 9, 1842, his opera premiered at La Scala in Milan, and in one fell swoop Verdi was a star throughout Italy. The Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves "Va, pensiero, sull'ali dorate" ("Climb, thought, on golden wings") struck a chord with Italians and became the unofficial national anthem of all who longed for a united Italy. The freedom of the country, which at that time was under the rule of the Austrian imperial family, suddenly seemed possible – and the 28-year-old composer became its symbolic figure. In the streets, the pubs and at home – everywhere people sang and whistled the melody. In the stores there were black hats, like the ones Verdi would wear and in the delicatessens there were 'Verdi pies' and pasta alla Verdi for sale.

As delighted as Verdi may have been with his first great success, he was later critical of it: "Since Nabucco, I have not had a quiet hour," he complained. In the years that followed, he wrote one opera after another, toiling "like a galley slave," driven by one thought: to earn enough money to retire and live in the countryside. That's what he finally did a few years later. Few people understood why Italy's most popular composer chose Busseto, of all places, an unspectacular village in the Po Valley, as the centre of his new life. This stretch of land between Parma and Piacenza is neither picturesque nor idyllic. In summer it is humid and muggy, in autumn dense fog hangs over the harvested fields. And when it starts to rain in winter, the Po floods the plain. So what made Verdi turn his back on metropolises like Paris, Venice or Milan at such a young age, from travelling, rehearsals and performances?

The hardships of being famous

Those who knew that Verdi came from Le Roncole, a small village near Busseto, thought that his deep attachment to his homeland was the reason. But it seems this was only half of the reason. Above all, the composer disliked the bustle that prevailed in big cities, especially in Paris. And so it is not surprising that the irritated maestro interrupted his stay in Paris in 1850 to purchase the Sant'Agata estate near his home town. There he was finally able to relax with his partner and later wife, the famous opera singer Giuseppina Strepponi. "It's a real pain in the ass to be famous. The poor little big men pay dearly for their popularity," he wrote to a friend. Verdi preferred the simple life: "I am and always will be a peasant of Roncole. I go to the fields. That is my occupation at present. The weather is fine and I walk from morning to night. It's a very prosaic life, but one feels good."

Verdi also enjoyed local cuisine: costoletta alla milanese, breaded veal cutlets fried in butter, was something he treated himself to at his favorite albergo in Cremona having finished his business at the cattle market. Verdi also loved pasta. He instructed his friend Cesarino De Sanctis to get plenty of it for the Christmas holidays: "As usual, I would like to ask you to send me: nine kilos of assorted long pasta and the thickest macaroni. Ten kilos of pastine, carmelline, annellini, etc. I ask for the highest quality!"

His cooks had to be able to prepare Genoese ravioli and cappelletti in brodo according to his liking. The maestro was considered a very demanding, difficult employer who was never satisfied with his "murderous cook". One by one, they left service. Whether out of necessity or passion – the Verdis often stood at the stove themselves. Verdi was an expert in cooking spalla cotta, boiled pork shoulder, a dish he had known since childhood. And since the gourmet always liked to have enough supplies at home, he particularly appreciated this simple dish. Because it is dried and salted, spalla keeps for many weeks. He would often give each guest a piece when they left.

As unfriendly as the maestro was often perceived, he had a good reputation as a host. The librettist Giuseppe Giacosa felt very much at home at Sant'Agata: "Verdi is not a reveller, but a gourmet; his table is hospitable, generous and understanding. Verdi feels at ease at the table." Especially when there was risotto alla Milanese. He discussed how to cook it with his composer friend Serafino De Ferrari in as much detail as he did music. But there wasn't much to discuss, because Verdi believed his way was the only way to prepare the dish.

Chianti instead of Lambrusco

Verdi knew how to present himself as a simple, modest peasant. When it came to culinary pleasures, however, he was not prepared to make any concessions. Not even when he travelled abroad. Parmesan cheese and culatello di zibello, the best ham in the region, were always in his luggage. When he left for St. Petersburg in 1861 to prepare the premiere of his opera The Power of Destiny, he took 20 bottles of Champagne and 120 bottles of Bordeaux for his personal use. The maestro knew what was good – and what was not. Although he grew Lambrusco at Sant'Agata, he did not sell it because it could not compete with the fine wines of Tuscany. In any case, he preferred to drink Chianti or Bordeaux than his own brand.

At last dolce far niente

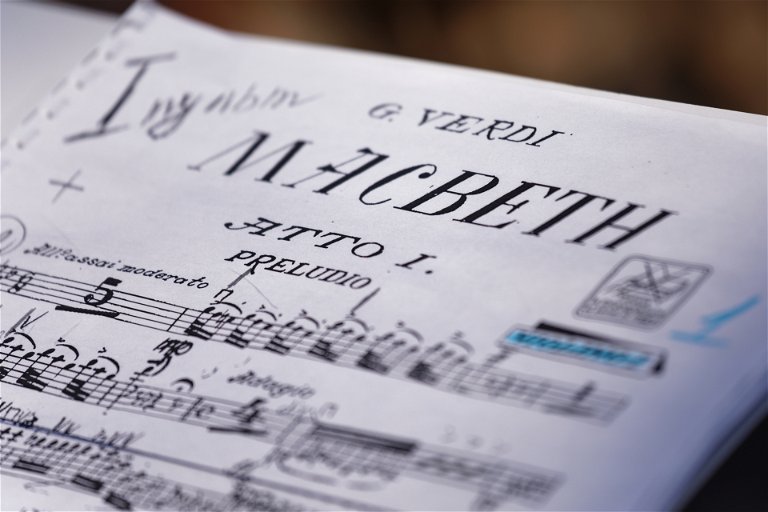

The maestro's visitors, who thought that music and composition were constantly being made and written at Sant'Agata, were soon disabused. Verdi remained immensely productive even after his move to the countryside – between 1851 and 1870 alone, he wrote Rigoletto, Il Trovatore, La Traviata, Sicilian Vespers, Simon Boccanegra, Un Ballo in Maschera, The Power of Destiny, Macbeth and Don Carlos. But after the premiere of Aida in 1871, written to celebrate the opening of Egypt's Cairo Opera House, Verdi increasingly lost the joy of composing and devoted himself more and more to his farming. It would take him 16 years to complete another opera, Otello, but he was not done yet. Gioachino Rossini, composer of the The Barber of Seville and a role model for Verdi throughout his life, died in 1868. Shortly before his death he had criticised Verdi, 21 years his junior, in a magazine, remarking that Verdi could "never write an opera buffa". A comment that deeply offended Verdi. So,at the age of 80, in February 1893, he brought his comic opera Falstaff to the stage of La Scala in Milan. The burlesque about an obese, vain, boastful knight, womaniser, buffoon and drunkard, became a huge success. Verdi was able to bid farewell to the opera world with a smile.

In 1897 Verdi's wife Giuseppina died, he himself four years later. The menu of his last dinner? Spring soup with gratin crust; grilled trout; beef tenderloin; asparagus spears; young turkey roasted on a spit; strawberry ice cream; patisserie and dessert. The Maestro remained a true epicure to the end.

Verdi and 'Falstaff'

"There is only one way to end better than with Otello: And that is to end victoriously with Falstaff," wrote librettist Arrigo Boito to the aged Giuseppe Verdi to convince him to compose an opera about the legendary bon vivant, glutton and rascal Sir John Falstaff. And the appeal did not miss its mark: "Dear Boito," the maestro replied, "Amen, so be it! Let's do Falstaff!" Verdi was not to regret his decision. Unlike his first comic opera, Un Giorno Di Regno, his second and last – the premiere was in 1893 – was an overwhelming success.

The plot of Falstaff is based on William Shakespeare's play The Merry Wives of Windsor (although librettist Boito also included scenes from Henry IV) and is about the down-and-out knight Sir John Falstaff, who approaches two married women in the hope that they will help him financially. But the ladies see through his dishonest intentions and lead him around by the nose. Verdi concludes the work with; "Tutto nel mondo è burla" or "Everything on earth is folly" – set as a fugue, a monumental masterpiece in the history of music.

After Verdi's death, the conductor and then music director of La Scala, Arturo Toscanini, studied the original Falstaff score and found a handwritten note by the composer: "The last notes of Falstaff. Everything is at an end! Go, go, old John. Run along your way as long as you can...Funny original of a villain; eternally true, behind any mask, at any time, in any place!!! Go...Go...Run, Run...Addio!!!"