The Wonderful World of Washed-Rind Cheeses

Munster, Époisses, Taleggio & Co are smelly little parcels of indulgence. Yes, washed-rind cheeses are strongly-flavoured but their bark is always worse than their bite.

The best way to enjoy a Munster cheese is in Munster itself, the pretty, red-roofed town which sits cosily in a valley of the Vosges mountains in northeastern France. Go there in the summer or early autumn, watch the cattle graze and savour the farmyard bouquet of the sticky pink-rinded cheese which is made from the milk of these cows. Lap up its flavours of smoky bacon, peanuts, damp straw and its indulgent, unctuous texture.

Munster is the patriarch of the pungent and divisive family of washed-rind cheeses: first made in medieval, northern French monasteries and now a familiar presence on cheeseboards in the shape of cheeses like Munster itself, Époisses de Bourgogne, Langres from Champagne-Ardennes and the eminently seasonal Vacherin de Mont d’Or.

The most important thing to know about washed-rind cheeses is that their bark is nearly always worse than their bite. If you are put off by that funky, intimate bouquet, it is worth pushing through and giving it a try, it will often be much milder than you might expect whilst still showing exciting complexity.

Like all traditionally made cheeses, washed-rinds are very much a product of place. While physical aspects like soil, climate and the local microbiome do play their parts, so does human culture. All cheeses, washed-rinds included, get their character from the nature of their surroundings and from the people who nurture them.

Bacteria and Brine

The distinctive magic of washed-rinds lies in their maturation. In their early stages, these cheeses are made in the same way as any other. Lactophilic bacteria – known as starter culture – is added to milk and converts the milk’s lactose into lactic acid. This acidification begins to separate the solids, the pale ivory curd, from the greenish liquid whey. Then rennet, an enzyme which coagulates milk, is added, separating out more of that whey and leaving a firmer curd. The curd is then ladled into pierced moulds which also give the cheeses their shape. Once the cheeses have drained enough, they are removed from their moulds and can be left to mature, developing their particular, complex flavours. Salt is normally added at some point when the curds are formed or after the cheeses come out of their moulds.

What distinguishes washed-rind cheeses is that they are washed in brine, or salt water, when they are still young, firm and rindless. The brine kills moulds such as Penicillium candidum, which creates the snow-white, fluffy coat of Brie, and Geotrichum fungus, responsible for that cheese’s complex flavours. At the same time, the brine provides the perfect environment for a family of bacteria called Brevibacterium linens, usually abbreviated to B. linens. B. linens helps to break down and soften the paste – the centre of the cheese – and creates the pink-orange rind with its characteristic and intense aroma.

Monastic Origins

This distinctive and often pungent family of cheeses, it turns out, evolved in mediaeval monasteries in northern France where mould-ripened cheeses like Brie were already common: modern Brie’s early mediaeval ancestors were the cheeses made in the smallholdings of northern France. The peasant farmers did not have large herds, so they collected milk over a number of days before devoting time to cheesemaking. During this period, the milk would sour naturally, creating a more acidic curd that did not welcome B. linens but favoured the growth of moulds. More importantly, mould ripened cheeses do not require much looking after as they mature, so multi-tasking peasant cheesemakers could just turn them now and again to prevent stickiness and control mould growth.

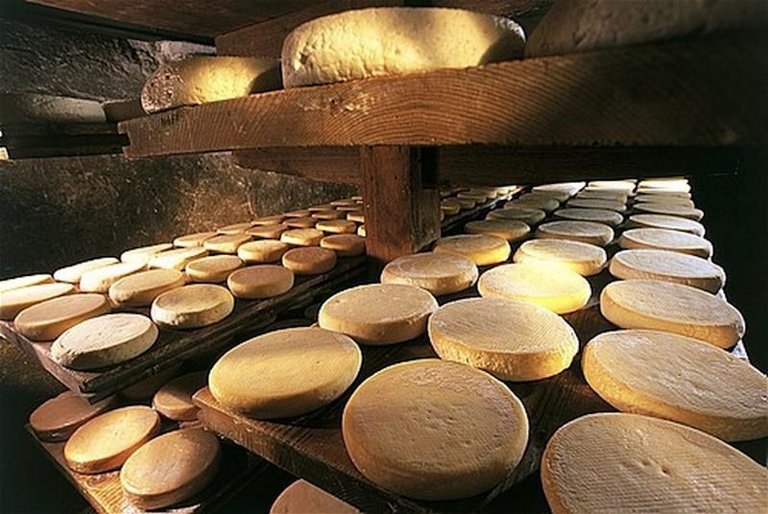

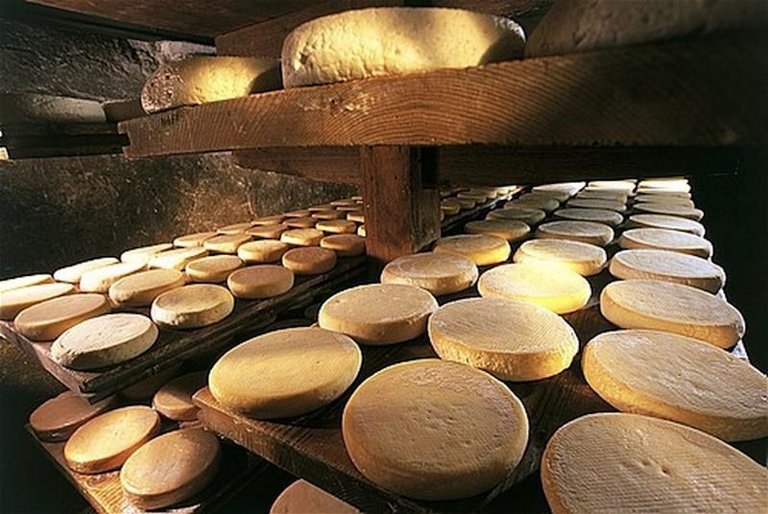

Cheesemaking in monasteries was another matter. Bigger herds meant more milk, lay monks meant available labour: cheese was made every day and the fresh, non-soured, low-acid curd was more welcoming to any passing B. linens. Monasteries were well-organised with plenty of specialised workers, herdsmen, brewers and bakers. Some monks thus specialised in making cheese and it is their experimentation and observation that lit upon the fact that moisture and salt would encourage particular rinds to grow. Then there is the attention it takes to wash the cheeses as they mature. You rest the cheese in the crook of your arm, dip your cloth into the brine and give the top and edges a gentle wipe, then turn the cheese over and wash its other side. Initially, this is done every couple of days, then once a week until it has reached its perfect condition.

The cool, moist, northerly cellars of the monasteries provided the perfect environment for B.linens to flourish, producing full-flavoured, pungent cheeses which likely felt like a blessing to the monks. At some point, someone tried washing the cheeses with beer instead. This treatment, at a later stage of maturation, offered even more flavour potential. This is why some cheeses are washed with local alcohol in the later stages of their maturation: Livarot is finished with Calvados, Époisses with Marc de Bourgogne.

Trading Cheeses

Washed-rind cheeses may have been born in France, but the comprehensive network of religious communities and monastic exchanges meant these cheese-making methods soon travelled to the abbeys of Britain and Ireland. Climatic conditions would have been similar. Ogbourne Priory in Wiltshire sent four thousand kilos of cheese a year to the Abbey of Bec in Normandy, and in 1242, East Anglian pirate Ranulph de Oreford plundered a ship from Rouen carrying, amongst other things, four large cheeses.

The full-fat and high-maintenance washed-rind cheeses made in Britain and Ireland were luxury goods destined for the abbot’s table, to feed him and his aristocratic guests. When King Henry VIII began the dissolution of the monasteries in 1536, these cheeses became too dainty: farms needed harder cheeses that would withstand the bumpy journey to market. In Britain and Ireland, along with abbeys and churches, shimmering illuminated manuscripts and breath-taking religious artefacts, washed-rind cheeses disappeared.

Today, the most famous washed-rind cheeses still come from France. Perhaps the best known after Munster is Époisses, named after a commune in the Burgundian department of Côte-d’Or. The tan-coloured rind shows the deep wrinkle of the Geotrichum fungus, which survives the salting, adding a pungent note and the sharp sting of ammonia, and creates a more liquid texture than Munster. Époisses is finished in Marc de Bourgogne, a powerful, fruity distillate made from grape skins left over from winemaking – a further local marker that adds to the character of this infamously aromatic cheese.

Between the Vosges and the Cote d’Or is the Langres Plateau, home of Langres cheese – a short pudgy cylinder with a cute little dimple in its top and a rosy, pink, wrinkled rind shading to tan with age. The centre of the cheese has a moist, crumbly texture, surrounded at full maturity with a softer creamy edge.

It is the custom to pour a measure of Champagne into the dimple before serving – an appropriate accompaniment indeed since Langres is in the historic department of Champagne-Ardenne. The salty air of Normandy provides a congenial environment for the washed-rind cheese Livarot, known as Le Colonel due to the reed bands that hold these fat little cylinders together and resemble the stripes of a French army colonel’s insignia. The old commune of Livarot is in the Calvados region and the cheeses are washed with that apple brandy which also provides an authoritative accompaniment.

Post-Modern

New styles of cheese

Though it seems modern methods of cheesemaking can transcend the physical conditions of any locality, washed-rind or any cheese is still a product of place. Local breeds, local drinks and local traditions still play their part. While the washed-rind family has travelled far in time and place, its fundamental character which evolved in the cool damp monastic cellars of northern France and the British Isles, remains the same, as does the human urge to innovate and experiment.

In 2015, Marcus Fergusson left his corporate job to make cheese in Somerset, England. Disinclined to try his luck against the great West Country Cheddar-making companies, he decided to invent a new style. His cheese, Renegade Monk, a sort of homage to stinky Burgundian cheeses, is a novel mixture of washed-rind and blue cheese. Renegade is part of a new family, a postmodern cheese, a child of the 21st century but with its roots firmly in the cellars of those early innovative monks working and praying in the Vosges Mountains and making their first experiments with brine, beer and cheese more than a thousand years ago.

Alpine Washed-Rinds

The French Alps are home to two more famous washed rinds. Vacherin de Mont d’Or has a singular, resinous flavour from the spruce band that holds this rather liquid cheese together, and a limited season – the cheese can only be made between August and March when the cattle are down from their Alpine pastures and cosied up in their winter quarters. It is ready to eat over the winter months and a seasonal treat when baked whole with thin slivers of garlic. Reblochon, on the other hand, made in the Haute Savoie, is melted whole over potatoes, bacon and cream to make tartiflette, a dish so absurdly indulgent only the French could have invented it.

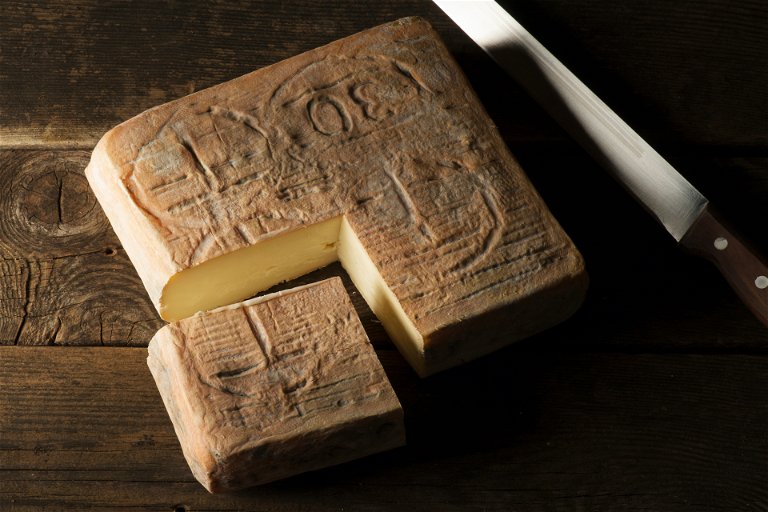

Belgium has also managed to preserve some monastic washed-rind cheeses like Chimay, La Ramée, and Maredsous, all still made by monks, and washed in the beers they brew. Italy is famous for two washed-rinds, both from Alpine regions: square-shaped Taleggio with a mild flavour that makes it an excellent starter washed-rind, and Fontina whose round wheels and concave sides are reminiscent of its French cousin Beaufort. Young Fontina makes a superb fondue.

Thanks to Henry VIII there are no traditional washed-rinds in Britain or Ireland, but the cheese renaissance which began in the 1970s, has given birth to cheeses like the Irish Milleens from County Cork, and the marvellously named Stinking Bishop from Gloucestershire England, among others.

Washed-rinds tend to be quite volatile and to be at their best should be eaten fairly swiftly. This doesn’t mean that you should throw it away when you feel it is past its prime. A favourite thing to do with end-stage washed-rind cheese is to melt it over sliced gherkins on a piece of sourdough bread – a sort of cheat’s raclette.

Pairing drinks with such characterful cheeses can be a challenge but there are plenty of options. Dry or off-dry whites with a full body have the weight to stand up to washed-rinds. Their slight sweetness makes a pleasing contrast to the cheeses’ salty umami flavours. Of course, you could try whatever the cheese is washed in, and if spirits like Marc or Calvados are too powerful, beer is always an option. Traditional English stouts and porters make wonderful partners for washed-rinds, the perfect match would be one of those strong, sweet Belgian beers. But whatever your preferred combination, do raise a glass to that semi-legendary monk who first started washing his cheese all those centuries ago.