The New Diversity of Argentinian Wines

Sub-regional differences and site-specific wines are changing the face of Argentina’s wine landscape. Plus tasting notes.

If you stood to the far north of Argentina and walked south at a consistent pace of 20km/12m per day, it would take you six months to walk all the way: having arrived, the biting winds brought by the Falkland Current might well be enough to convince you to turn north and walk back again. Along the way you would pass close enough to the equator to shake hands with Apollo, stand in the shadows of the awe-inspiring Andes mountains, navigate rainforests, broad rivers and soaring temperatures before eventually finding yourself in the wind-swept plains of the south.

It would be a breathtakingly beautiful journey across all 3,650km/2,268m of this kaleidoscopic country, and one likely well provisioned: Argentina is rightly famed for its food, and even more so for its wine. It’s been almost 500 years since vines were first planted by Spanish conquistadores. Centuries of artisanal production, not to mention waves of European immigration, have left a deeply embedded wine culture in regions scattered across the country. An economic and political crisis towards the end of the 20th century was poorly timed but ultimately helped to galvanise an industry ready to present itself to the international market.

The Making Of Malbec

Argentine wine has often been condensed into a single word: Malbec. While accounting for just over 20% of total plantings, this ambassador grape has shed its French accent entirely and become the standard bearer for its adopted country. Vast vineyards owned by a few producers in the traditional wine regions of Mendoza have long been responsible for most of the wines found in your local supermarket aisle. The inky, teeth-staining colour, the gentle caress of velvety tannin and the vanilla-tinged, plummy fruit are hallmarks of baking hot days and cool nights, coupled with no small amount of tinkering in the winery. Better still, these wines are affordable, can be enjoyed young and you would be hard pressed to find a better pairing for a traditional Argentine asado.

Yet for all this well-deserved success, the winds of change are blowing across the vineyards of Argentina. Not only are a new generation of wine-makers keen to showcase the true diversity of Argentine wine, but wine lovers are just as excited to share the journey.

Whilst producers were traditionally keen to extol the virtues of planting at altitude, the focus is now on identifying differences between sub-regions and individual vineyards, vine ages, trellising choices, soil types and structures. Identifying the latter is no mean feat; more soil pits have been dug in the single vineyards of Mendoza than in entire regions elsewhere in the world. Research and development projects are more likely to focus on understanding the differences of microbiological activity in the vineyards than they are to make winery operations more efficient. New oak has never been less fashionable whilst concrete, cement and clay are all being utilised to produce fresher, more transparent wines.

With so much attention to differences in the vineyard, it’s perhaps no surprise to find a far greater diversity of grape varieties now sharing the limelight. Malbec has taken on a more dynamic, multi-faceted role while Cabernet Franc, Pinot Noir, Petit Verdot and Semillon are all thriving across the country. Grapes that were previously considered experimental plantings are now being listed by suitably impressed sommeliers across the globe. Trosseau from Patagonia and Tannat from Salta were unlikely to have been on anyone’s radar even a decade ago.

The North

The dry, arid north of Argentina is home to just a small percentage of Argentine vineyards. As a result of the extreme climate, the wines are some of the most recognisable. Jujuy, Salta, Catamarca and Cafayate all cluster between 23-26 degrees latitude from the equator, thus planting at high altitudes is essential to help mitigate the scorching, daytime heat.

Whilst Salta and Cafayate are well established, partly due to pioneers like Bodega Colomé – one of Argentina’s oldest wineries and the first producers to plant above 3,000m/9,840ft in the world – Jujuy and Catamarca are relatively new on the Argentine wine scene. The soils here tend to be light and sandy and plantings soar to new heights. In the town of Uquía (Jujuy), a vineyard perched on the now disused Moya mine reaches 3,320m/ 10,890ft above sea level, and is one of the highest vineyards in the world.

Due to the intense UV-radiation, barely dispersed on its journey through the unpolluted air as it reaches these elevated vineyards, the red wines in these regions tend to be particularly vivid and dark in hue. Malbec still reigns supreme but increasingly finds itself plucked from the vine earlier and earlier, with alcohol levels now rarely breaching 14.5%. The white Torrontés grape is at the height of its powers here: its intense, floral aroma heightened by the bright sunshine, its acidity preserved by the cool nights, with many producers experimenting with oak fermentation to add an extra layer of texture and depth to an already fascinating style of wine. Another interesting development is the steadily increasing plantations of the red grape Tannat, a firm favourite in neighbouring Uruguay, which seems to particularly thrive in the hot weather of Valles Calchaquies.

Central Regions

The central regions of Argentina are also known as Cuyo, after the native peoples that inhabited this area prior to the arrival of the Europeans. Pressed against the Andes Mountains lies La Rioja, San Juan and Mendoza; between them, they account for 95% of wine produced in the country.

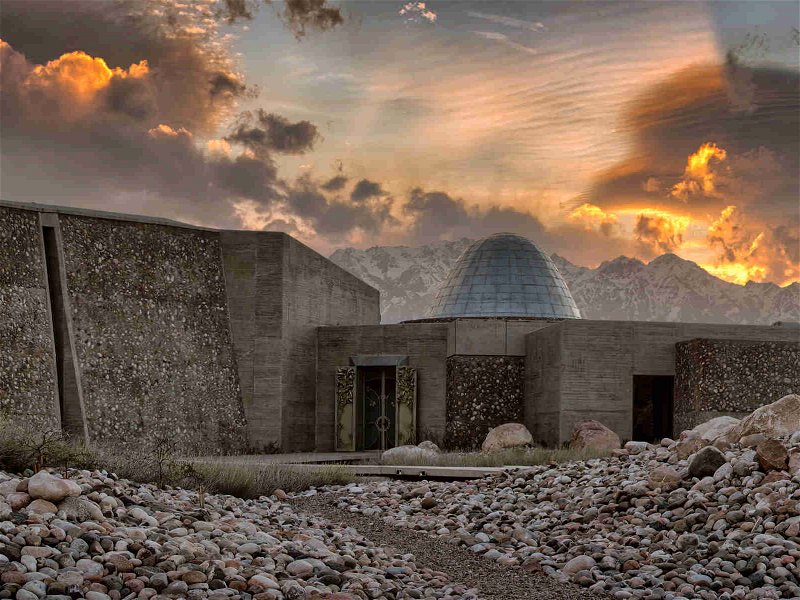

Nowhere have the changes in Argentine wine been more apparent than in Mendoza. As a single entity, it is one of the world’s largest wine regions. For decades, it was the only geographical name commonly featured on wine labels. In reality, Mendoza is a region of 18 different communes, hours apart, the vivid, snow-capped Andes serving as a constant backdrop.

Most wineries are still located within the traditional zones of Maipu and Lujan de Cuyo, but much of the excitement is directed further south, to the Uco Valley and its sub-regions. Producers now distinguish between wines made with fruit from Vista Flores, La Consulta, Gualtallary and San Carlos. Individual vineyards across Mendoza now frequently take pride-of-place on wine labels, driven by terroir-centric producers like Zuccardi and Altos los Hormigas. Even single plot wines are being produced, such as Catena Zapata’s White Stones and White Bones Chardonnays, a result of the incredible research into soil differences between individual vineyards.

Malbec is arguably at its very best in the higher reaches of the Uco Valley; vibrant, sappy, more textural than powerful, the sweet crunch of tannin a welcome treat. Cabernet Franc excels too, particularly in the stony, poor soil of Gualtallary in Tupungato, where fruit ripeness is combined with floral and herbal notes retained by cool nights. Firm yet aromatic Chardonnay is being produced in the highest vineyards, at 1,450m/ 4,757ft above sea level, whilst cedar-scented Cabernet Sauvignon relishes the constant heat of Maipu. It is only a matter of time before the best of these regions become recognised in their own right.

The South

Most of Argentine viticulture relies on high altitude plantings to mitigate intense daytime temperatures, but further south the dynamic changes. The Andes are lower and cooling breezes sweep across the land from the Pacific, bringing rain and humidity. Soils are richer and provide grazing land for cattle. The subregions of La Pampa, Neuquen, Rio Negro, Chubut and Trevelin account for barely 2% of the country’s vine plantings between them.

If there is a future for an entirely new style of Argentine wine, it is likely to hail from these cooler, southerly regions. Vibrant, pure-fruited Pinot Noir is made across Patagonia. Matias Riccitelli makes uncompromisingly fresh Semillion and ethereal Trosseau in Rio Negro, from old vines that bid their time in secret for more than 50 years. The most southerly vineyards in the country, perhaps the world, belong to Bodega Otronia. Wines are labelled Patagonia Extrema for good reason: the average temperature is cooler than in Chablis. Crisp Riesling, textural Pinot Grigio and steely Chardonnay retain vivid brightness, indelibly marked by the unforgiving climate. Spearheaded by many of its most famous winemakers and families, this is not a nod to fashion but the ongoing quest for the truth. The jewels of Argentina are found all across the country, in old vines, treasured vineyards; the soil of Argentina itself. They do not sit side by side as in Burgundy or Champagne in France but are tucked away in corners of a country as vast as it is beautiful. It’s a journey worth taking. Argentine wine has never been as exciting or dynamic as it appears today.